From 1921 Coup to Modern Protests: Iran's Pahlavi Legacy Debate Resurfaces Amid Unrest

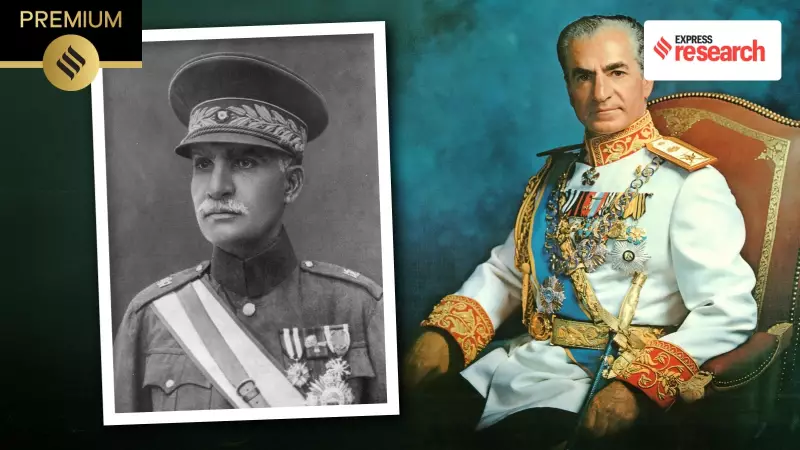

As anti-government protests challenge the Islamic Republic of Iran, the legacy of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his father, Reza Shah, is being fiercely debated across the nation and among observers worldwide. The name of Reza Pahlavi, the 65-year-old son of Iran's last monarch living in exile in the United States, has resurfaced amid Iran's latest wave of protests, widely described as the most serious nationwide challenge to the Islamic Republic in decades.

The Historical Irony of Pahlavi Resurgence

Iranian philosopher Ramin Jahanbegloo told The Indian Express that for the last 47 years, the Pahlavi monarchy "has always been there as a strong alternative to the Islamic regime, especially in the minds of younger people." This moment carries significant historical irony, as the last comparable mass mobilisation in Iran culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi monarchy itself, which ruled the country from 1925 to 1979.

The dynasty emerged from early 20th-century instability and intense power rivalry among great powers, presiding over rapid modernisation alongside deep political repression. It combined ambitious nation-building with authoritarian rule and constant reliance on foreign support, creating a complex legacy that continues to influence Iranian politics today.

Setting the Stage for Pahlavi Rule

Before the Pahlavis came to power, Iran was ruled by the Qajar dynasty, which governed the country since the late 18th century. By the turn of the 20th century, Qajar authority had weakened considerably, leading to a chaotic political situation. Unlike its longstanding neighbour, the Ottoman Empire, Iran failed to modernise its military, leaving it vulnerable to foreign intervention.

During World War I, despite having declared neutrality, Iran became a theatre of conflict among major Western powers. Historian Michael P Zirynsky noted in his paper "Imperial Power and Dictatorship: Britain and the Rise of the Reza Shah, 1921–1926" that overrun by foreign powers, nearly a quarter of Iran's population died during the war. "Neutral Iran suffered a greater proportionate mortality than did any belligerent country, except perhaps Serbia," Zirynsky observed.

The Rise of Reza Shah Pahlavi

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Anglo-Russian understanding in Iran collapsed. Britain, alarmed by the spread of Bolshevik influence and its possible implications for India, sought stability along Iran's northern frontier. It was in this context that Reza Khan, a senior officer in the Persian Cossack Brigade, emerged as a key figure.

In February 1921, he led a military coup in Tehran that many historians believe was encouraged by the British. Following the coup, Reza Pahlavi was appointed commander-in-chief of the Iranian army. By 1923, he had become prime minister himself, and two years later, through careful political manoeuvring, he overthrew the Qajar dynasty and was crowned Shah of Iran.

Reza Pahlavi projected himself as the heir to Iran's ancient imperial past. At his coronation in 1926, the crown placed on his head was reportedly modelled on that of the fourth-century Sassanian king Shapur the Great, symbolising his connection to Persia's glorious history.

Modernisation and Authoritarianism Under Reza Shah

Reza Pahlavi is best known for his modernisation drive, deeply inspired by the reforms of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey. Under his 16-year rule, the Shah undertook rapid modernisation efforts including:

- Creation of a centralised bureaucracy and national army

- Development of railways and roads infrastructure

- Establishment of a secular legal and education system

- Promotion of Westernisation through dress reforms

- Curtailment of clerical authority

Jahanbegloo recalled that his grandmother, who came from a traditional background, was forced to abandon her headscarf and instead wear a hat and manteau, illustrating the profound social changes implemented during this period.

However, Reza Shah ruled through authoritarian means. Political parties were suppressed, the press silenced, and parliament weakened in the name of order and national unity. "The ruling elite was liberal-minded, but the regime itself was not liberal," Jahanbegloo noted, highlighting the contradiction at the heart of Pahlavi rule.

The Reign and Fall of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi differed sharply from his father in temperament and upbringing. Educated at an elite Swiss school, he spoke English and French and had a more Western orientation. Jahanbegloo observed that the younger Shah was "terribly indecisive, and naive"—traits that were largely responsible for the monarchy's collapse in 1979.

After World War II, Mohammad Reza increasingly aligned himself with the United States, which replaced Britain as the principal guarantor of his regime. American support became especially critical after the 1953 coup that removed then-prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who had spearheaded Iran's oil nationalisation.

Mohammad Reza continued his father's modernisation project, though in a less overtly coercive manner. Nevertheless, repression persisted through the notorious secret police force SAVAK, which became infamous for torturing political prisoners and suppressing dissent. Secularisation policies further alienated the Islamic clergy, creating powerful opposition forces.

The 1979 Revolution and Contemporary Relevance

Over time, opposition to the Shah coalesced across ideological lines. Leftist groups and the Islamic right, otherwise deeply divided, converged in their rejection of the monarchy and Western influence in Iran. This alliance culminated in mass protests that swept Iranian cities in early 1978, paralysing the state and eroding the regime's authority.

In January 1979, the Shah and his family fled the country, ending more than five decades of Pahlavi rule. Three months later, Iran was declared an Islamic Republic, with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini assuming power as its first Supreme Leader.

Nearly half a century later, as Iranians once again take to the streets in widespread protests, the legacy of the Pahlavis has returned to public debate. This time, it appears not as a relic of the past but as a contested alternative in an uncertain present. The current protests have revived discussions about Iran's political future, with the Pahlavi monarchy representing both a symbol of modernisation and authoritarianism in the national consciousness.

The historical parallels between the 1979 revolution and contemporary protests are striking, yet the political landscape has evolved significantly. Younger generations who never experienced Pahlavi rule firsthand are now engaging with this historical legacy, creating new interpretations of Iran's complex political history as they seek alternatives to the current Islamic Republic.