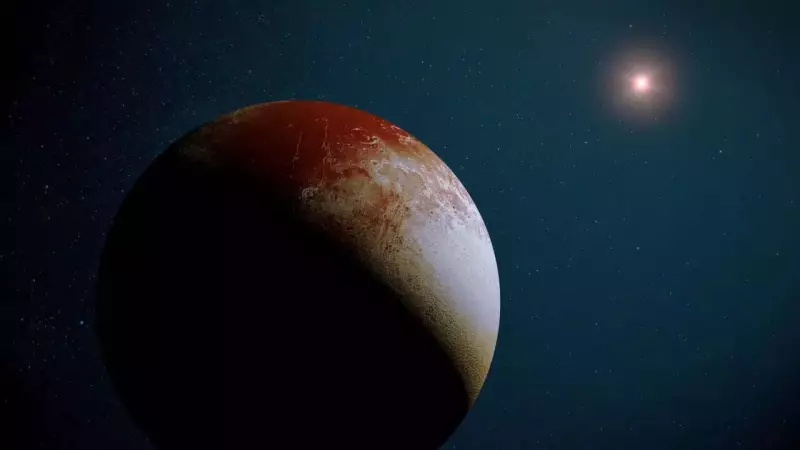

In a significant astronomical breakthrough, Pluto's largest moon Charon has become the focal point for understanding how small celestial bodies formed and evolved in the outer Solar System. The unique relationship between Pluto and Charon, where they orbit a shared center of mass located outside Pluto's surface, distinguishes them from typical planet-moon systems and has long puzzled scientists.

The Cosmic Dance Begins: Early Kuiper Belt Environment

During the early formation of our Solar System, the Kuiper Belt was a crowded neighborhood filled with numerous icy bodies moving through overlapping orbits. Pluto traveled as a mid-sized object with sufficient gravity to disturb nearby paths, while Charon formed independently rather than from material surrounding Pluto. The region's crowded conditions increased the likelihood of close encounters, particularly at relatively low speeds where gravitational interactions could significantly alter long-term trajectories.

The limited sunlight at this distance reduced solar tide influence, giving Pluto greater ability to affect passing objects. These factors created an environment where temporary captures were possible, though most encounters didn't develop into long-term orbital partnerships. For Charon, the combination of relative proximity, repeated encounters, and gradual orbital migration created conditions where a short-lived gravitational hold could transform into a lasting association.

The Capture Mechanism: How Charon Became Permanent

For Charon to become permanently bound to Pluto, it needed to lose substantial orbital energy. Research published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society examined how three-body encounters, where a third object interacted with Pluto and Charon during close approach, could extract excess energy from Charon's path. This interaction would have shifted Charon onto a slower, altered trajectory, increasing chances it would remain near Pluto rather than escaping back into heliocentric orbit.

After this initial capture, repeated close passes between Pluto and Charon generated strong tides that distorted both bodies' shapes. These tidal bulges acted as friction sources, converting orbital motion into heat and gradually reducing the system's overall energy. Over time, Charon's orbit became more circular and tightly bound, transforming a chaotic encounter into the stable gravitational relationship observed today.

Perfect Harmony: The Pluto-Charon Binary System

One of the system's most striking features is its high angular momentum, greater than expected if Charon had formed from simple debris. Capture models suggest this angular momentum came from the geometry of the initial encounter. If Charon approached Pluto at a glancing angle rather than directly, gravitational exchange would have transferred rotational energy to both bodies.

This process placed Charon into a rapidly evolving orbit while speeding Pluto's rotation. As tidal forces continued acting, rotational energy redistributed, causing Charon's orbit to expand while Pluto's spin slowed. NASA's New Horizons mission revealed surface and interior structures aligning with long-term tidal activity, supporting that the system's rotational state reflects ongoing adjustments beginning during capture. Eventually, both bodies became tidally locked, each perpetually showing the same face to the other.

Why This Research Matters for Understanding Distant Worlds

The capture model remains influential because it aligns with modern measurements of density, orbital distance, and rotational behavior. Other binary systems in the Kuiper Belt also show high angular momentum and relatively equal-sized components, suggesting capture events may have been common during the region's early history.

By studying how Pluto captured its largest moon, researchers gain crucial insight into broader Solar System dynamics and conditions that shaped numerous small worlds. The Pluto-Charon system provides a valuable reference point for understanding how gravitational encounters, energy loss, and tidal evolution combine to create lasting binary configurations at the edge of the Sun's influence.