In a significant escalation of cultural controls, authorities in China's Xinjiang region have declared dozens of Uyghur-language songs "problematic," warning residents that downloading, playing, or sharing them online could lead to imprisonment. This crackdown targets a core aspect of Uyghur identity, extending even to traditional folk music played at weddings for generations.

Official Warnings and Banned Expressions

According to an exclusive recording obtained by The Associated Press from the Norway-based nonprofit Uyghur Hjelp, a meeting was held in the historic city of Kashgar in October last year. Police and local officials informed attendees that possessing or distributing banned songs was a criminal offense. The popular folk love song "Besh pede" was specifically listed among the prohibited content.

Officials at the Kashgar meeting also instructed residents to avoid common Muslim greetings. They were told to replace the traditional farewell phrase "Allahqa amanet" (May God keep you safe) with "May the Communist Party protect you." This directive underscores a broader campaign to suppress religious expression among the predominantly Muslim Uyghur community.

Prison Sentences and a Pattern of Repression

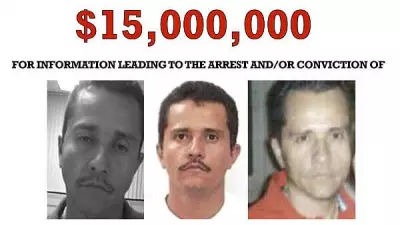

The policy is not an empty threat. The AP obtained the court verdict for Uyghur music producer Yashar Xiaohelaiti, 27, who was sentenced in 2023 to three years in prison and fined 3,000 yuan ($420). His crime: uploading 42 "problematic" songs to his account on the NetEase Cloud Music streaming service and downloading eight banned e-books.

Interviews with former Xinjiang residents corroborate the crackdown. One former official described a family friend sentenced to over ten years in prison for playing traditional Uyghur instruments and singing songs. Several audience members were also sentenced. In another incident, two teenagers were reportedly detained simply for sharing a Uyghur song on WeChat.

This renewed focus on cultural expression suggests a continuation of the repressive policies that have defined Xinjiang for the past decade. Between 2017 and 2019, at least 1 million Uyghurs and other minorities were extrajudicially detained in camps, according to rights activists and foreign governments. In 2022, a UN report accused China of human rights violations in Xinjiang that might constitute crimes against humanity.

What Makes a Song "Problematic"?

Authorities in Kashgar played a message warning against seven categories of banned songs. The list includes:

- Traditional folk songs with religious references: Like "Besh pede," which uses romantic tropes invoking God (e.g., "Oh, God, I love you!"). Ethnomusicologist Professor Rachel Harris notes the song does not incite extremism.

- Songs "inciting terrorism, extremism and smearing CCP rule": This includes "Yanarim Yoq," based on a poem by imprisoned Uyghur poet Abduqadir Jalalidin, and "Atilar" (Forefathers) by detained musician Abdurehim Heyit.

- Music from the diaspora: Newer tunes created by Uyghurs living abroad.

- Formerly state-sanctioned music: Shockingly, the pop song "As-salamu alaykum," which aired on the state-run Xinjiang Television talent show "The Voice of the Silk Road" in 2016, is now banned for "forcing people to believe in religion."

A common thread is that many banned songs were written or performed by Uyghur cultural figures who are now imprisoned. Elise Anderson of the New Lines Institute states that association with these individuals alone renders the music "dangerous" in the eyes of authorities.

China's Narrative and the "New Normal"

The Chinese government defends its policies as necessary for counter-terrorism and stability. After sporadic violence in previous decades, Beijing intensified its campaign post-9/11. A Foreign Ministry statement said China "cracked down on violent terrorist crimes" in accordance with the law and blamed "anti-China forces" for maliciously hyping Xinjiang issues.

Following international backlash, China claimed in late 2019 that the detention camps were closed. It now promotes Xinjiang as a tourist destination. However, experts like Rian Thum, a senior lecturer at the University of Manchester, argue that repression continues in more subtle forms.

Less conspicuous controls include expanded Mandarin-only boarding schools separating children from families and random phone checks for sensitive material. The ban on music and everyday greetings points to a policy of long-term cultural control and assimilation, normalizing a climate of fear where even a soulful folk song can be a path to prison.