In the heart of modern Bengaluru, where crowds now cheer for sporting heroes, lies a history submerged by time. The Sree Kanteerava Stadium, a city landmark since 1946, stands on what was once the bed of the seasonal Sampangi Kere. This transformation from a vital waterbody to a concrete sports arena mirrors the city's dramatic evolution from a pensioners' paradise to a bustling tech metropolis.

The Seasonal Lake and Its Lost Ecosystem

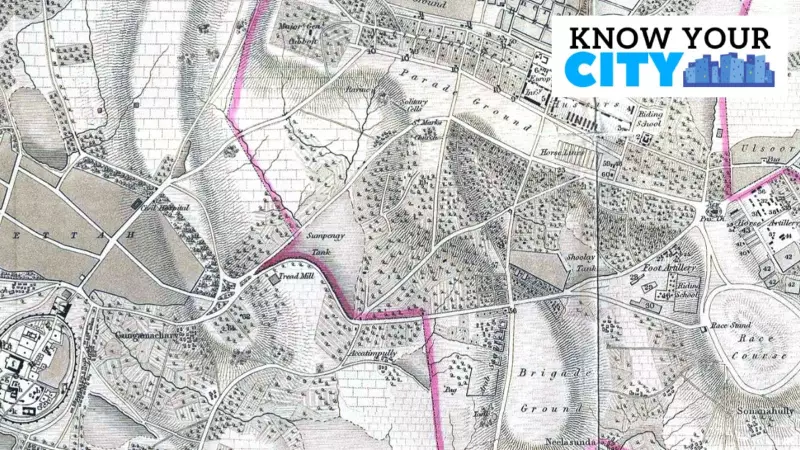

Historical evidence, including a clear 1854 map by Pharaoh & Co labeling it the "Sumpengy Tank," confirms the lake's existence. According to Dr. Hita Unnikrishnan, an assistant professor at the University of Warwick and visiting faculty at Azim Premji University, Sampangi Lake was originally a rain-fed, seasonal waterbody. Like most lakes in Bengaluru, it would dry up during the summer months.

This seasonal cycle supported a unique way of life. Oral histories record that before colonial times, local communities would cultivate crops on the fertile dried lake bed. When the monsoon arrived, the lake would refill, returning to its natural bounds. The water supply was further supplemented by several temple tanks, only one of which survives today.

Dr. Unnikrishnan explains that the colonial era brought systemic change. "With the advent of colonialism and long-distance water supply, people were no longer as dependent on waterbodies," she notes. This shift, coupled with the introduction of sewage into the lakes, altered their fundamental nature, turning them from seasonal basins into perennial, polluted pools.

The Vannikula Kshatriya Community and Colonial Conflict

Research, including the paper 'Contested Urban Commons,' documents the deep connection between the lake and the local Vannikula Kshatriya community. Elders recalled the area being surrounded by fertile farmlands. The lake was so abundant with fish that the excess catch was used to fertilize crops.

This community's legacy is still honored; the last remaining tank of the Sampangi Lake is a stop on the sacred Karaga festival procession, a tradition initiated by the Vannikula Kshatriyas. The lake itself sat on a significant border, between the British-ruled cantonment and the old walled pete (city) under Mysore rule.

Conflicts over the lake's use soon emerged. While local horticulturists wanted more water stored for irrigation, the British administration began restricting native activities. By 1884, an order was passed against brickmaking near the lake. A decisive turn came in 1895 when the administration decided against storing more water as its main feeders had been cut off.

Pressure also came from wealthy residents of nearby bungalows and users of a polo ground, who feared flooding. These actions marked the beginning of the lake's decline, setting the stage for its eventual disappearance.

From Swamp to Stadium: The Final Transformation

Deprived of its water sources and function, Sampangi Lake degenerated into a swampy, mosquito-ridden area. By 1937, a large portion had been drained. The space was first converted into a carnival ground, a temporary use that paved the way for a permanent structure.

Shortly after, the construction of the Sree Kanteerava Stadium began, cementing the lake's fate. The stadium opened in 1946, replacing a community-centric natural resource with a public sports and entertainment venue.

Today, apart from the small tank in the Karaga procession, the memory of Sampangi Lake surfaces ironically during Bengaluru's heavy rains. The stadium and its surroundings are prone to waterlogging, a ghostly reminder of the land's original purpose as a catchment for monsoon rains.

The story of Sampangi Lake is a microcosm of Bengaluru's environmental and urban history. It highlights a profound shift from a landscape managed around seasonal water bodies to one shaped by colonial priorities and later, by the needs of a growing modern city, often at the cost of its ecological heritage.