In a discovery that has left marine biologists baffled, a team of scientists found sharks living inside one of the world's most active and dangerous underwater volcanoes. The finding, made in 2015, challenges fundamental assumptions about where complex marine life can survive.

The Unexpected Discovery Inside a Volcanic Crater

An expedition led by ocean engineer Brennan Phillips set out to study the Kavachi submarine volcano, located near the Solomon Islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Known for its frequent and violent eruptions that spew lava, ash, and highly acidic water, Kavachi was considered a hostile environment where only the hardiest microbes could exist.

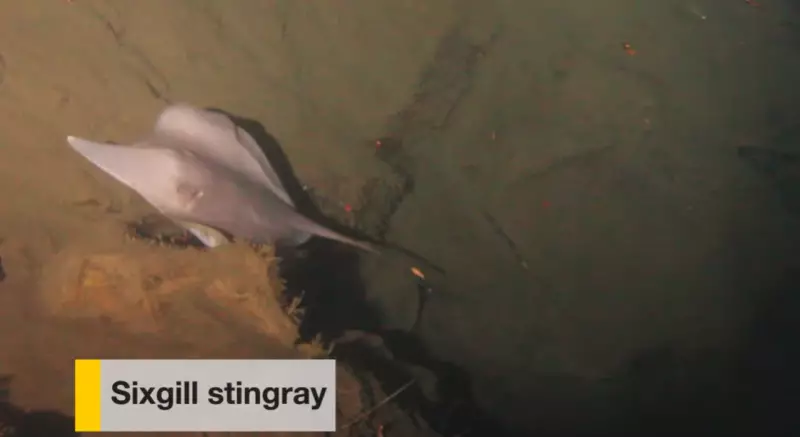

During a period of volcanic calm, the team deployed a deep-sea camera into the volcano's crater, a large depression known as a caldera. After retrieving the camera an hour later, they reviewed the footage and were met with an astonishing sight. Hammerhead sharks and silky sharks were swimming calmly through the hot, acidic waters. A stingray was also spotted, possibly sheltering in a cave-like feature within the caldera.

"The animals appeared completely unfazed by the conditions," Phillips noted, expressing surprise at seeing large predators in a place where life seemed impossible.

Kavachi Earns the Nickname 'Sharkcano'

The footage, later released by National Geographic, captured global imagination, and the volcano was informally dubbed 'Sharkcano'. This nickname perfectly captured the bizarre and extreme nature of the discovery. The mystery deepened in 2022 when NASA satellite imagery confirmed that Kavachi had erupted again, following earlier eruptions in 2007 and 2014.

This raised a critical and unresolved question: Did the sharks and other animals survive these violent eruptive events? "Do they leave? Do they have some sort of sign that it’s about to erupt?" Phillips wondered, highlighting the central puzzle of their behaviour.

Robotic Follow-Up Missions and Lingering Questions

Due to the extreme danger, subsequent research relied on expendable, low-cost robotic systems. A team including Alistair Grinham and Matthew Dunbabin returned to Kavachi with robots small enough for carry-on luggage. These devices confirmed the harsh environment, recording surface pH drops and water temperatures up to ten degrees higher than normal.

"One unexpected result was the eruption forced fresh material from the vent to be embedded into the robot itself," Dunbabin said, turning a loss into a unique method for collecting rock samples.

Experts acknowledge that, biologically, Kavachi should not support animal life. The water is hot, acidic, and turbid—conditions terrible for most fish. Yet, the sharks were seen darting in and out of the volcanic plumes. Researchers speculate they may have unique physiological adaptations or behavioural instincts that warn them of imminent eruptions.

Studying these resilient sharks could provide crucial insights into how marine species might cope with extreme environmental stress, including rising ocean temperatures due to climate change. For now, the question of how and why they call an active volcano home remains, as Phillips put it, "a lingering question mark."