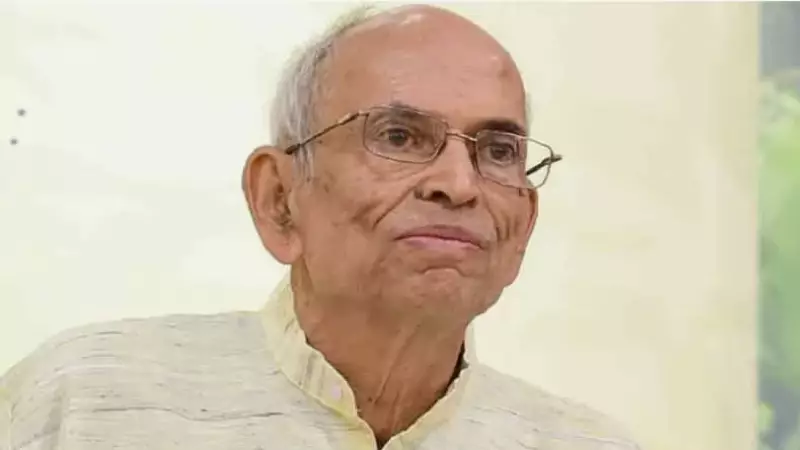

Prominent ecologist Madhav Gadgil has delivered a sharp critique of large-scale mining operations in Goa, arguing that this extractive model of development has caused irreversible harm to the environment while primarily benefiting a small, privileged elite. In his writings, Gadgil points to severe ecological degradation, the loss of sacred community sites, and widespread illegal and corrupt practices.

Sacred Groves and Villages Under Siege

Drawing from his visits to affected villages, Gadgil provides a grim picture of local communities struggling against environmental ruin. He specifically recounts his observations in Cavrem village in Quepem taluka, which is surrounded by mining sites.

The closest mining lease, he notes, is on 'Devapan Donger'—a hill that holds a sacred grove. The villagers expressed deep distress as the mining lease encompasses this entire area, which is dedicated to the deity Kashi Purush. Gadgil documented their concerns, which include rampant tree-cutting in forest areas and the loss of precious medicinal plant resources due to mining activities.

Systemic Failure and the Konkan Railway's Legacy

Gadgil, leveraging his decades of experience as an environmental impact assessment expert, did not mince words about governmental awareness. "It was impossible that govt was not aware of high levels of illegal mining and corrupt practices that caused much environmental damage," he wrote in his book 'A Walk Up the Hill: Living with People and Nature'.

He also revisited his 1992 ecological assessment of the Konkan Railway project. While celebrated for connecting the western coast, Gadgil describes a different reality on the ground. He highlights the case of Carambolim lake, once a picturesque bird habitat, which was ruthlessly cut through by the railway, substantially reducing its water spread and degrading its ecological value.

Broader Ecological Consequences

The ecologist further emphasized that the railway construction disrupted Goa's traditional brackish water management systems (khazans). These systems served as crucial nursing grounds for fish and acted as natural barriers against sea encroachment. The damage, he implies, is part of a pattern where development projects overlook long-term environmental sustainability and local ecological knowledge.

Through the Goa Govt Joint Development Committee, Gadgil organized meetings with major mining companies to discuss these impacts directly. His account stands as a powerful indictment of a development model that prioritizes extraction over ecological and social health, leaving communities to grapple with the consequences.