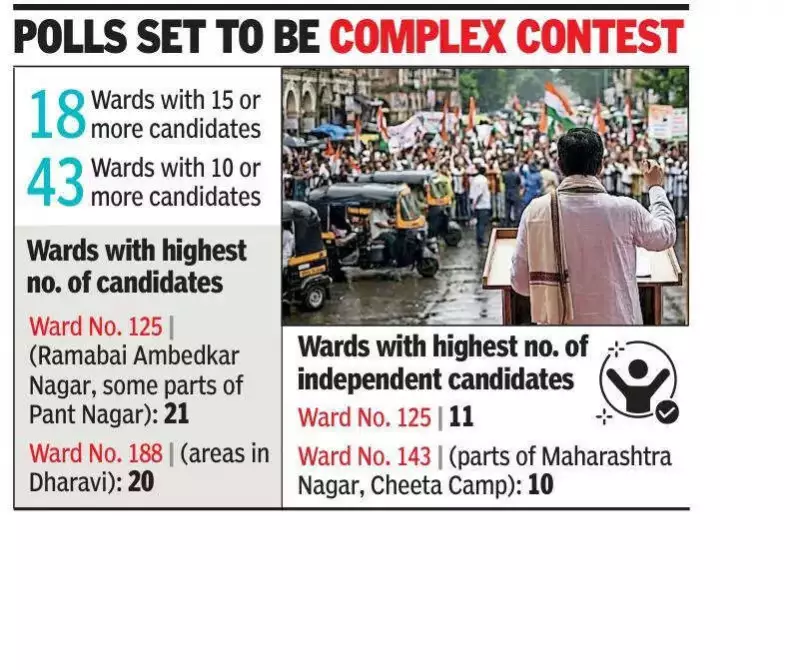

The upcoming elections for the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) are witnessing an unprecedented surge in the number of candidates, particularly in specific pockets of the city. Data from the nomination process reveals a complex electoral battlefield, with a high concentration of hopefuls in areas with homogeneous voter profiles.

A Crowded Ballot: The Numbers Behind the Surge

Electoral data highlights a significant trend: 18 wards in Mumbai now have 15 or more candidates each, complicating the contest. In six of these wards, the number of contestants has even exceeded the technical limit of 16 names per ballot unit. This influx includes a mix of independent candidates, alongside those from national parties, regional outfits, and smaller political formations. Notably, some of these smaller groups have limited organisational roots in Mumbai but draw influence from other states.

Why So Many Candidates? Experts Decode the Trend

Political analysts point to multiple factors driving this proliferation. Mrudul Nile, a professor of political science at Mumbai University, attributes it to internal factions within parties and the political fragmentation of certain communities. "In areas dominated by homogeneous, socio-economically disadvantaged voters, every party fields its candidates," Nile explained. He also noted that bigger parties sometimes field proxy candidates, and some individuals contest to ensure their candidature is considered for future elections.

Nile added that while the field seems crowded, this fragmentation often works to the advantage of larger, established parties, making it difficult for independents or lesser-known candidates to secure victory. "Aspirations among the lower socio-economic groups also leads to an increased number of candidates," he stated.

Echoing this, political scientist Surendra Jondhale observed that contemporary elections see many individuals with political aspirations. "People with a bit of money and net worth consider contesting elections, while some look at it as a tool to earn money," Jondhale said. He pointed out a troubling practice in some areas: "Many also think that they can buy votes in slum pockets to get elected even if they do not secure tickets from parties."

High Stakes in Disadvantaged Areas

The concentration of candidates is notably high in slum clusters, Dalit-dominated neighbourhoods, and Muslim pockets. Bhiwandi MLA Rais Shaikh highlighted why the stakes are higher here: the civic body plays a crucial role in the daily lives of residents. "For some of the candidates, contesting elections is a way of getting recognition for themselves," Shaikh noted.

Activist Anil Galgali cited additional reasons, including the delay in conducting elections and the aspirations of both older and younger generations. "Some are worried that they might be deprived of a chance next time due to dynastic politics or nepotism," Galgali said. "Some think that they can resolve local problems only by becoming a corporator, and others look at it as a way to earn fast money."

This phenomenon underscores a vibrant yet complex democratic process in India's financial capital, where local governance intersects directly with community identity and socio-economic aspirations, often resulting in a fiercely competitive and crowded electoral arena.