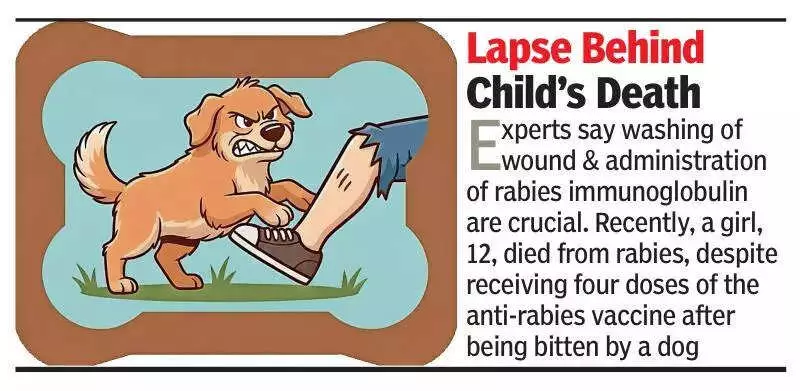

The tragic death of a 12-year-old girl in Bengaluru from rabies has starkly revealed a deadly loophole in standard medical protocol for dog bite victims. The child succumbed to the virus weeks after being bitten, primarily due to the critical omission of Rabies Immunoglobulin (RIG) during her initial treatment, a mandatory step for severe wounds.

A Fatal Omission in Mandatory Care

Despite receiving four doses of the anti-rabies vaccine after the incident, the young girl eventually developed paralytic rabies and died at a city hospital. Medical experts have clarified that the vaccine alone is insufficient to stop the virus if Rabies Immunoglobulin is not administered promptly for high-risk injuries. The victim had sustained a Category-3 dog bite on her right leg, characterized by skin puncture where the dog's saliva enters the wound. RIG, which works by neutralizing the virus at the wound site before it can travel to the nervous system, was not given.

Specialists from the Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health (IGICH), where she was later treated, emphasized that complete post-exposure prophylaxis is non-negotiable. "Rabies prevention is effective only when complete post-exposure prophylaxis — wound-washing, vaccine, and RIG — is administered," the doctors stressed. This three-step protocol is the global standard for preventing the fatal disease.

Challenging Diagnosis and Progressive Symptoms

Nearly two months after the bite, the girl was admitted to IGICH with symptoms including low-grade fever, progressive weakness in both legs, vomiting, and headache. Her condition deteriorated rapidly, leading to difficulty walking, sitting, and urinary retention. Notably, she did not exhibit classic rabies signs like hydrophobia (fear of water), seizures, or altered behavior initially, which complicated the diagnosis.

Doctors initially considered other neurological conditions such as acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM), Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS), and acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). It was only by the ninth day of hospitalization that she developed altered sensorium, dystonic limb movements, and loss of brainstem reflexes. Suspicion of rabies encephalitis led to saliva PCR tests, which confirmed the infection after being conducted three times.

Dr. Vykunta Raju Gowda, a paediatric neurologist at IGICH, explained the diagnostic challenge. "Diagnosis of rabies encephalitis can be challenging, especially in its paralytic form, as it may masquerade as other neurological disorders... In this case, the absence of typical symptoms such as hydrophobia, along with progressive motor weakness, neurogenic bladder, and dystonia, made the diagnosis more complex," he said.

The Critical Gap in Access and Awareness

The reason for the crucial lapse in administering RIG remains unclear. The family has stated they were not informed about its necessity. A British Medical Journal (BMJ) case report on this incident suggests that RIG might not have been available in the rural area where she first sought treatment. This points to a severe systemic issue: a critical gap in access to complete rabies prophylaxis in certain regions, turning a preventable tragedy into a fatal outcome.

Dr. Gowda added that this case underscores the need for heightened clinical suspicion for rabies in children presenting with progressive lower limb weakness. More importantly, it reinforces the absolute necessity of timely and complete post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent such rare but invariably fatal outcomes. The incident serves as a grim reminder that in the fight against rabies, every single step of the protocol is vital, and any omission can have irreversible consequences.