For decades, Bengaluru did not demand the spotlight in films. It existed quietly in the background—within shaded avenues, unassuming houses, college campuses, and meandering talks. Particularly in Kannada cinema, the city was never merely a setting; it represented an entire ethos. In the classic Mayor Muthanna, the legendary Dr Rajkumar arrives in Bengaluru as an anonymous villager, possessing no wealth or connections, armed solely with his principles. The city does not reject him; it embraces him. Bengaluru provides the space for him to evolve, find his voice, and ultimately rise to become its Mayor. While idealistic, this narrative captures a timeless truth about the city: Bengaluru has historically been a destination where people arrive to forge their identity.

The Cinematic Shift: From Moral Compass to Neutral Stage

Contrast this with the recent film Aavesham, starring Fahadh Faasil as Ranga. His character also arrives rootless, but without any moral restraint. Bengaluru absorbs him as well, yet the result is far more sinister. Leveraging the city's anonymity, Ranga transforms into a powerful real estate mogul and a strongman. If Mayor Muthanna portrayed Bengaluru as a moral enabler, Aavesham presents it as a neutral amplifier, equally capable of magnifying virtue and vice. The journey from Muthanna to Ranga maps Bengaluru's own cinematic evolution—from a gentle, value-driven space to a restless and contradictory urban giant.

Chronicling the Metropolis: Key Films That Defined Bengaluru

Kannada cinema has meticulously documented this urban transformation. In the 1980s, Mani Ratnam's Pallavi Anu Pallavi depicted a modern, emotionally complex Bengaluru where apartments and silent streets reflected loneliness. Ravichandran's Premaloka later presented a youthful, aspirational city focused on love and desire. Director Upendra then disrupted this narrative with films like A and Upendra, turning Bengaluru into a loud, confrontational, and sexually charged arena that exposed societal hypocrisy.

As migration and the IT boom reshaped the city's reality, films adapted. Mungaru Male offered a romantic and vulnerable Bengaluru, while Gaalipata highlighted its magnetic pull of familiarity. The city became a mood—restless and intimate. Later, Lucia used urban anonymity to explore psychological breakdowns, and Ugramm hinted at a buried, gritty underbelly. The harsher facets of crime and survival emerged in films like OM, Jogi, Duniya, and Aa Dinagalu.

Recent years have seen even sharper realism. Bheema mainstreamed Shivajinagar's street slang, making language a tool for survival. Made in Bengaluru focused on migrant aspiration, portraying the city as transactional yet hopeful. Movies like Sapta Sagaradache Ello, Kavaludari, and Godhi Banna Sadharana Mykattu reflect the emotional dislocation in a rapidly changing urban landscape.

The Missing Narrative and Non-Kannada Perspectives

Director-producer Tharun Sudheer points out a gap: the story of Bengaluru's burgeoning upper-middle class, particularly the tech professional earning around ₹70,000 a month, remains largely untold. This demographic, deeply affected by policy changes, now defines the city's new social fabric, and cinema has yet to fully tap into its stories.

Beyond Kannada, other language films interpret Bengaluru differently. In Kamal Haasan's Kalaignan, the weather itself becomes a character. Tamil films like Ullam Ketkume and Paiyya use the city for introspection. Malayalam cinema often shares an emotional bond, exemplified by Bangalore Days, where the city is a warm, liberating space for youth. Aavesham, a Malayalam film, sharply subverts this image, portraying a volatile, masculine Bengaluru shaped by underground power dynamics.

Director Manasa U Sharma notes a telling detail: the period film Aachar & Co, set in old Bengaluru, had to be shot in Mysuru because finding a suitable heritage house in modern Bengaluru was too difficult—a stark symbol of the city's physical and cultural transformation.

The Enduring Truth: A City That Absorbs

Film scholar and director KM Chaitanya identifies two primary cinematic engagements with cities like Bengaluru: one where the protagonist is the city's victim, and the more dominant narrative where one conquers and rules the urban "monster." He cites Accident as a turning point for shifting the cinematic gaze to North Bengaluru, later followed by the authentic portrayal of the city's underbelly in Aa Dinagalu.

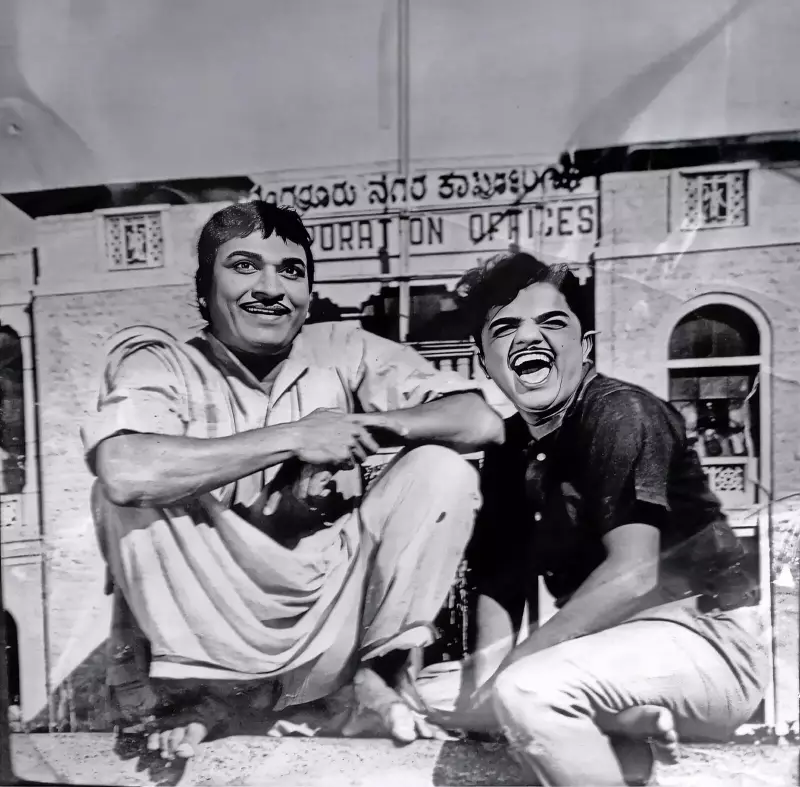

Through the decades, from the disciplined warmth of Dr Rajkumar's films and the everyday humour in Shankar Nag's and Anant Nag's middle-class worlds, to today's complex portraits, one constant remains. Bengaluru does not impose a single identity. It absorbs all—ambition and idealism, village sensibilities and metropolitan dreams, integrity and raw aggression—and reflects them back on screen, offering a compelling mirror to its own relentless evolution.