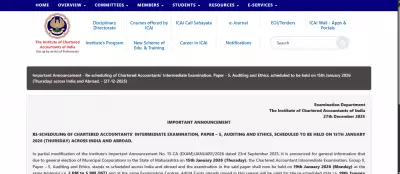

In a bid to foster a robust reading culture and address growing concerns over digital overexposure, the governments of Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan have recently mandated daily newspaper reading sessions in schools. This policy shift has ignited a debate among educators, psychologists, and policy experts on its potential to not only build literacy but also act as a counterbalance to pervasive screen addiction among children.

Morning Rituals in Delhi's Classrooms

The concept, however, is not entirely new in India's capital. For decades, several schools in Delhi have seamlessly woven newspaper reading into their daily routines. At Birla Vidya Niketan in Pushp Vihar, the day begins with a 45-minute DEAR (Drop Everything and Read) period. Students from classes 4 to 12 huddle over student-edition newspapers, with teachers guiding discussions on headlines and vocabulary.

"This is all to promote current affairs and general knowledge," explains Principal Minakshi Kushwaha. The school even uses "chocolate questions" on current events as incentives. Similarly, at The Indian School in Sadiq Nagar, the 'zero period' is dedicated to newspaper-based learning for classes 3 to 12. Principal Tania Joshi highlights its multifaceted role: "It's not only for knowledge or to encourage reading, but also to help children connect concepts."

English lessons come alive through newsprint, with senior students practicing report writing and younger ones circling nouns and solving crosswords. Joshi notes an observable shift: "I've noticed children turning to more books in their free period as compared to before we started the newspaper reading exercise."

Government Schools and the Funding Challenge

The scenario in Delhi's government schools presents a contrast. While not mandated by the state, the practice is encouraged. Ajay Kumar Choubey, principal of a Sarvodaya Bal Vidyalaya, says headlines are read during assembly by a selected student. He believes newspapers are a "very powerful instrument" that can reduce screen time's impact.

However, a key hurdle remains funding. Choubey and other teachers recall that government schools once subscribed to junior newspaper editions, but the practice stopped when funding dried up. This has led to a diluted form of the initiative, especially with the aggressive push towards smart classrooms, as noted by Delhi University's Latika Gupta.

Expert Opinions: Hope, Skepticism, and Nuance

The policy's claim of curbing screen time meets both optimism and caution from experts. Clinical psychologists offer a positive perspective. Dr. Kamna Chhibber of Fortis Healthcare explains reading acts as an "effective habit replacement" in a screen-saturated environment. Dr. Bhavna Barmi, a child psychologist, adds that structured school reading routines can spill over to homes, improving self-regulation and even sleep patterns by reducing evening screen use.

Education experts, however, urge tempering expectations. Punam Batra, a professor at Delhi University, calls the automatic screen-time reduction claim a "tall order," stating there is no research proving physical newspaper reading reduces screen addiction. She also voices skepticism about newspapers being neutral tools, suggesting a more meaningful intervention would be to turn children from news consumers to producers.

Latika Gupta agrees that while beneficial, newspaper reading cannot be projected as a cure for screen dependence. She emphasizes, however, that print allows for deeper, more patient engagement than digital scrolling. Professor R Govinda, instrumental in drafting the RTE Act, downplays concerns of politicization, noting children engage with news differently based on their age.

The Policy Push and the Road Ahead

The recent government orders mark a formal recognition of this pedagogical tool. The Uttar Pradesh government's December 23 order introduced a 10-minute "news reading" slot in morning assemblies explicitly to "curb excessive screen time." Rajasthan has followed with a similar mandate.

The journey in Delhi's classrooms shows that the success of such mandates hinges on consistent access to age-appropriate materials (like student editions), teacher training, and sustainable funding—especially for government schools. While it may not be a silver bullet for screen addiction, the decades-old practice underscores the enduring value of print in cultivating focused reading habits and connecting young minds to the world beyond the glow of a screen.