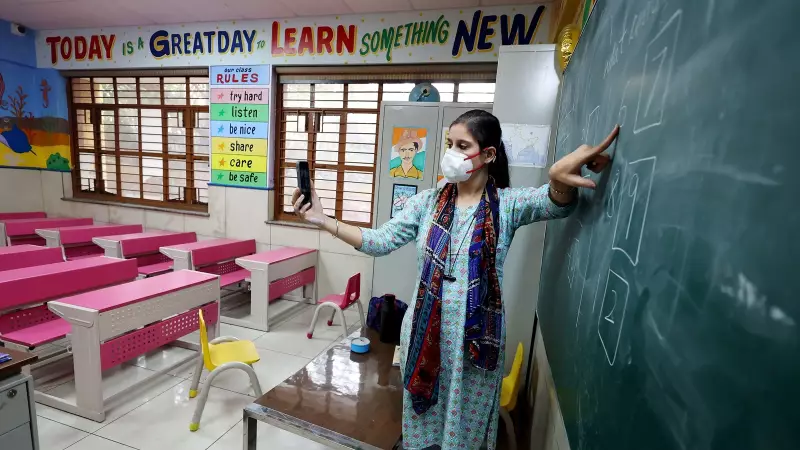

For the third consecutive winter, schools across Delhi and the National Capital Region (NCR) are once again oscillating between physical, online, and hybrid modes of instruction. This recurring shift, triggered by dangerously poor air quality and the enforcement of the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP), is exacerbating the deep learning scars left by the Covid-19 pandemic, educators report.

The Heart That Looks Like a Potato: Science Suffers Online

The consequences of this unstable learning environment are most palpable in subjects that demand hands-on experience, logical reasoning, and consistent practice. Naina Nagpal, a Class 10 biology teacher at Modern Public School in Shalimar Bagh, provides a stark example. She typically uses a detailed three-dimensional model to teach students about the human heart. However, in hybrid mode, plagued by network lags, that model blurs and distorts on her laptop screen.

"It starts looking like a potato," Nagpal says, describing how her immersive 3D class collapses into a confusing 2D presentation. Students end up memorising terms without grasping the underlying concepts. This problem extends to chemistry and biology experiments, which are now merely demonstrated on camera for remote learners. "The child studying online is not doing it. They are only watching," Nagpal emphasises, highlighting the passive nature of virtual science education.

An Unequal Classroom: The Human Cost of Hybrid Mode

The hybrid model, where a single teacher simultaneously instructs students in a physical classroom and others attending online, creates an inherently unequal learning space. Teachers admit that their attention is inevitably divided, often favouring the children physically present.

"As a human being, I will always give more attention to the child sitting in front of me," says Ritu Sharma, a senior coordinator and English teacher at ITL Public School. The first casualty in this setup is meaningful interaction. Students attending online, often with cameras switched off, remain silent when confused, while teachers lose the vital ability to read non-verbal cues—the puzzled look or distracted stare that signals a need for help.

The foundational cracks are even wider for younger students. Rupi, a Class 5 teacher, recalls a lesson on evaporation where students physically present observed bowls of water placed near a window and under a fan. One online student, facing repeated connection drops, missed the entire process. When later asked why the water disappeared, she wrote: "Because the teacher removed it." For primary education, where learning is experiential, such gaps are critical.

Deepening the Pandemic's Legacy: Stamina, Writing, and Home Pressures

Educators stress that the learning deficits they are witnessing now did not exist before the pandemic. Pre-Covid, short school closures for weather did not fracture the learning continuum. The post-Covid classroom, however, is grappling with a host of new challenges.

"The biggest difference is stamina," Sharma notes, pointing out that even senior students now struggle to sit through a full school day. Writing and language skills have taken a severe hit, with the instant, in-person correction of errors vanishing in the online realm. Debjani Das, head of the English department at Amity International School, Saket, confirms this sharp decline in writing fluency.

Hybrid learning also assumes a supportive home environment that many children lack. Teachers report receiving calls from working parents apologising for not being home during online sessions and requesting "extra care." For older students, home can be a source of emotional turmoil, family conflict, or financial stress—issues that often surface only in the safe space of a physical classroom. "Trust has to be built before learning can happen. That is almost impossible on a screen," Sharma asserts.

Seeking Solutions Beyond the Screen

While most schools have not officially lowered academic standards, teachers are quietly compensating through remedial classes and extra sessions. However, the erosion of skills like handwriting, a product of muscle memory lost during prolonged typing, is harder to address.

Academic experts like Latika Gupta of Delhi University's Department of Education argue that hybrid mode "completely trivialises what education actually is." She warns that the constant interruption prevents recovery from pandemic-era learning loss, a situation disproportionately affecting girls, who may be pulled into household chores during home-based learning.

Teachers and experts are calling for a fundamental re-prioritisation of physical schooling. Suggestions include modifying winter schedules—perhaps reducing hours—instead of suspending in-person classes altogether. Some, like Naina Nagpal, propose redesigning the academic calendar to front-load critical, hands-on content during months with better air quality. The consensus is clear: normalising hybrid education is not the solution. The path to recovery lies in reclaiming the integrity, equality, and human connection of the physical classroom.