In Maharashtra, the humble jowar, known locally as jwari, is far more than just a cereal. It is a cultural cornerstone and a historic symbol of resilience, often called the lifeblood of the Deccan plateau. However, the latest agricultural data from the state paints a deeply concerning picture for this vital crop.

Extreme Weather Decimates Key Jowar Belt

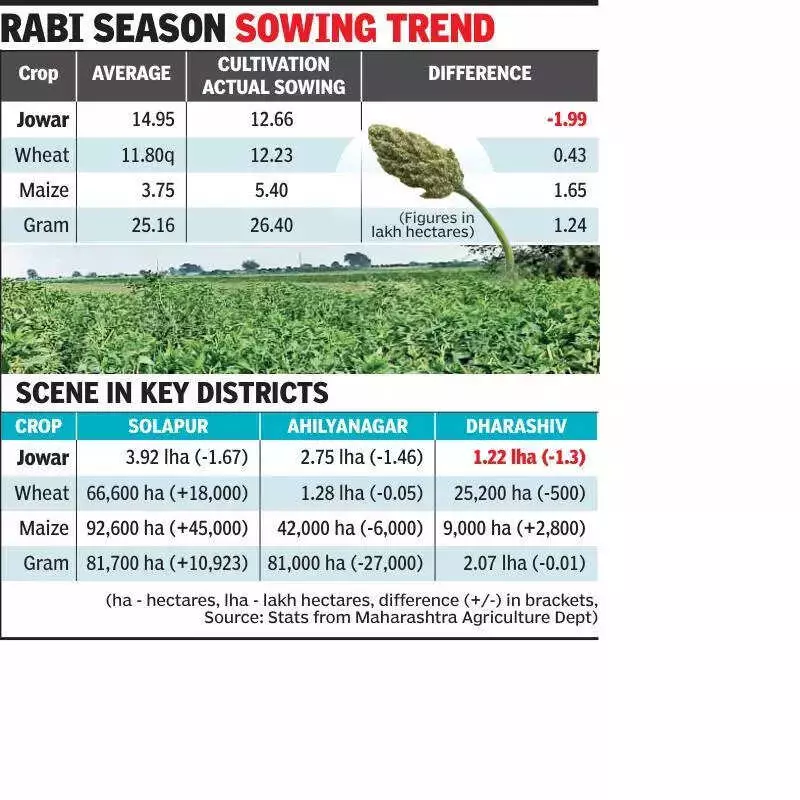

Official statistics from the Maharashtra agriculture department reveal a sharp and worrying decline in jowar cultivation this rabi season. The total area sown has shrunk by nearly 2 lakh hectares, falling from an average of 14.95 lakh hectares to just 12.66 lakh hectares. The districts of Solapur, Ahilyanagar, and Dharashiv, which collectively contribute about one-third of the state's jowar output, have borne the brunt of this collapse.

The primary culprit was an exceptionally destructive monsoon. These regions experienced floods and rainfall exceeding 200% above normal levels. The relentless downpour left farmlands submerged for weeks, even after the monsoon season ended. This critical waterlogging forced countless farmers to miss the entire rabi sowing window for jowar, a crop that is predominantly rain-fed and perfectly adapted to the state's drier regions.

Farmers Forced to Abandon a Traditional Staple

The scale of loss is staggering at the district level. Solapur recorded a drop of 1.67 lakh hectares under jowar. Ahilyanagar saw sowing reduce by 1.46 lakh hectares, and Dharashiv registered a decline of 1.3 lakh hectares. Farmers like Bharat Sadu Dattu from Mangalwedha tehsil in Solapur had no choice but to switch to other crops.

"I abandoned jowar and chose to grow kardai (safflower) on two acres where the fields were severely affected by heavy rainfall," Dattu explained. "On the remaining three acres, although I sowed jowar, I fear productivity will dip sharply." His yield expectations tell the story of devastation: from a harvest of nearly 60 quintals from five acres in the past, he now anticipates a mere 15 to 20 quintals this year.

This shift has impacted even premium varieties. Mangalwedha is famous for the GI-tagged Maldandi jwari, prized for the unique flavour it gives to the traditional bhakri. This variety requires about four-and-a-half months to mature fully. With one to two months lost due to unworkable fields, many growers opted for faster alternatives like wheat, maize, or gram.

Rising Prices and Shifting Agricultural Patterns

The dramatic reduction in supply is already sending shockwaves through the market. Wholesale prices for jowar have surged over the past two months. Grain merchant Sadanand Korgaonkar from Kolhapur reported a sharp increase of nearly Rs 7 per kg, with wholesale prices now ranging between Rs 55 and Rs 60 per kg. Retail prices are hovering close to Rs 70 per kg.

"Most of our jowar comes from the Barshi market in Solapur. With lower production this season, prices are only expected to climb further," Korgaonkar added. This price hike directly impacts consumers across Maharashtra, where nearly half of all households consume bhakri at least once daily. The growing awareness of millets' nutritional benefits had already boosted demand, making this supply crisis even more acute.

Statewide data confirms a major crop substitution trend. As jowar acreage contracted, farmers turned to other options. Sowing area for wheat increased by 43,000 hectares, maize by 1.65 lakh hectares, and gram by 1.24 lakh hectares. In the key jowar-producing districts alone, nearly 80,000 hectares were diverted to these alternative crops.

The decline of jowar represents more than an agricultural shift; it threatens a cultural and nutritional mainstay. The soft, white grains, valued for their high gluten content that gives bhakri its signature texture, are becoming less accessible. This crisis underscores the vulnerability of even the most resilient crops to the increasing volatility of climate patterns.