The story of India's partition in 1947 is etched in blood and trauma, but few chapters are as poignant as the fate of Lahore. This vibrant city, a cradle of culture and commerce, did not fall to Pakistan by design or destiny, but was rather sacrificed on the altar of political expediency and cartographic uncertainty. The tale unfolds not on the battlefield, but in the quiet, tense rooms where the Radcliffe Line was hastily drawn.

The Map Room Gamble: Radcliffe's Impossible Task

Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a British lawyer with no prior experience of India, was given the monumental and impossible task of drawing the new borders between India and Pakistan. Arriving in July 1947, he had just five weeks to carve up the subcontinent. The Punjab Boundary Commission, tasked with deciding Lahore's fate, was deeply divided. The two Indian judges argued passionately for Lahore's inclusion in India, while the two Pakistani judges insisted it belonged to Pakistan.

The Indian case was strong. The district of Lahore had a 60.62% Muslim population, but the city itself was a cosmopolitan hub. Crucially, the tehsils of Kasur and Chunian, with clear Muslim majorities, lay to its east. The Indian argument was one of contiguity and administrative unity: if these eastern tehsils went to Pakistan, the Indian districts of Ferozepur and Zira would be severed. To keep Ferozepur's crucial canal headworks, a trade-off was implied. Lahore, despite its Muslim plurality, became the bargaining chip.

Radcliffe, under immense pressure and with zero room for local nuance, made his solitary decision. He awarded the Muslim-majority eastern tehsils to India to protect Ferozepur's water infrastructure. In return, Lahore, though not demographically decisive, was ceded to Pakistan. It was a cold, cartographic calculation. The city's deep historical and cultural ties to undivided Punjab, its status as a center of education, arts, and commerce for all communities, counted for nothing in this rushed division.

The Human Catastrophe Unfolds

The announcement of the Radcliffe Award on August 17, 1947, two days after Independence, triggered one of history's greatest human tragedies. For the large Hindu and Sikh populations of Lahore, the city they called home was suddenly a foreign land. Overnight, they became targets in a newborn nation that defined itself by faith.

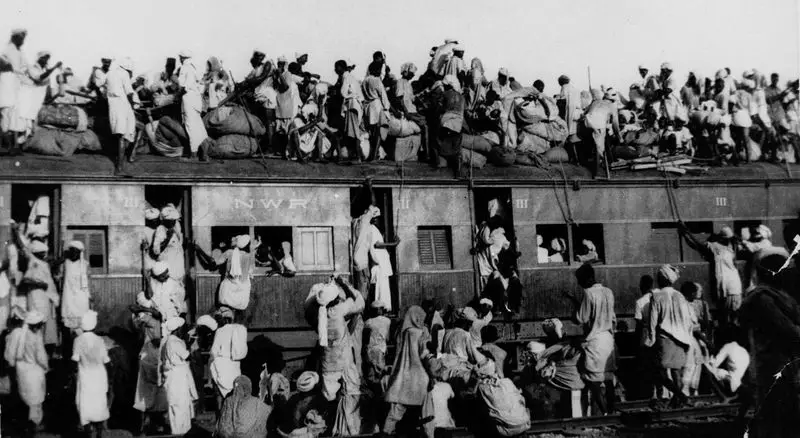

A mass exodus began. Trains filled with refugees became rolling coffins, arriving at stations in Amritsar and Delhi laden with corpses. The violence was reciprocal and brutal, but the loss of Lahore symbolized a profound cultural amputation for India. Libraries, institutions, and ancestral homes were abandoned. The writer Bhisham Sahni, who fled Lahore, later captured this trauma in his seminal novel "Tamas."

The city's sacrifice created a domino effect of displacement and bitterness. Properties were lost, families were torn apart, and a shared heritage was fractured. Lahore's inclusion in Pakistan was not a validation of the two-nation theory's clean sweep, but a stark reminder of its messy, violent reality. The city's diverse character was a casualty of the line Radcliffe drew in his map room.

A Legacy of Lingering Questions

The decision on Lahore continues to resonate decades later. It raises enduring questions about the arbitrariness of borders drawn by distant arbiters. Was the protection of canal water truly worth the loss of a millennia-old cultural capital? Could a different configuration, perhaps a referendum, have spared the bloodshed?

Historians like K.C. Yadav and accounts from the time suggest the outcome was never a foregone conclusion. It was a product of last-minute political pressures, strategic considerations about resources, and the overwhelming rush to meet the British deadline for withdrawal. Lahore was not won; it was effectively traded.

Today, Lahore stands as a major Pakistani metropolis, but its history is a palimpsest of its undivided past. The story of 1947 reminds us that its current nationality was born from a complex calculus of sacrifice and uncertainty. The city's fate is a permanent testament to the human cost of partition, a cost paid not by politicians in Delhi or Karachi, but by the millions who called it home and were forced to leave everything behind.