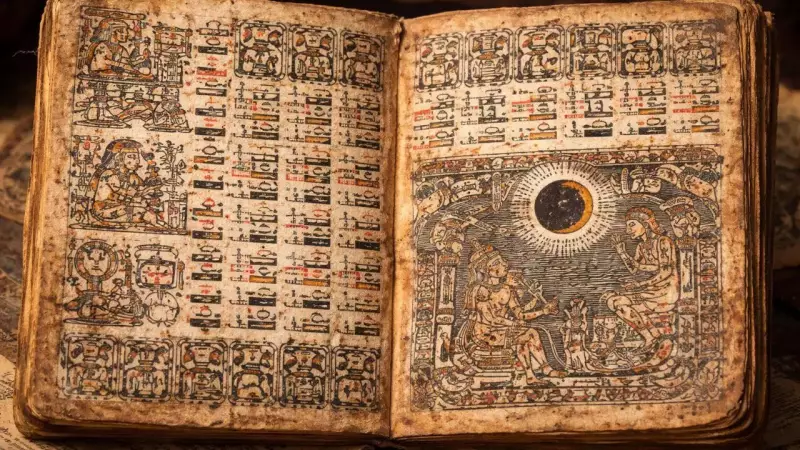

The Dresden Codex: A 1,000-Year-Old Maya Manuscript That Still Predicts Solar Eclipses

It appears almost miraculous that a manuscript dating back a millennium could still accurately forecast solar eclipses. The Dresden Codex, one of only four surviving books from the ancient Maya civilization, contains a sophisticated system capable of flagging eclipses centuries before they occur. This remarkable document is far more than mere decoration or ritualistic artifact—it represents a functional astronomical tool meticulously crafted by ancient scholars.

Decoding the Ancient Eclipse Prediction System

As highlighted in Discover Magazine, the codex features numerous folded pages filled with numerical data, lunar cycle records, and specific eclipse markers. Ancient scribes maintained and updated this document across generations, correcting errors and resetting cycles as needed. While many assume pre-Columbian science was purely symbolic, this manuscript demonstrates that careful astronomical observation and long-term mathematical calculations were integral to Maya daily life.

The Dresden Codex has remarkably survived centuries of time, conquest, and natural decay. Scholars including John Justeson from the University at Albany, SUNY, have studied its intricate tables and identified a structured methodology for tracking lunar months and predicting eclipses.

The Mathematical Precision Behind Maya Astronomy

The eclipse table within the codex follows a 405-lunar-month cycle, marking 69 critical lunation moments when the new moon aligns near the lunar nodes—precisely the conditions necessary for solar eclipses. Although not every marked date guaranteed a visible eclipse in all locations, this system provided Maya calendar specialists, known as daykeepers, with advance warning to prepare rituals and document celestial events.

Tracking 405 lunar months presented significant challenges, as days naturally drift and errors accumulate over time. However, the Maya astronomers didn't leave accuracy to chance. They developed overlapping tables with reset points at 358 months and 223 months, creating correction mechanisms for both minor and major drifts.

Modern researchers have modeled this system and discovered it could maintain prediction accuracy within 51 minutes over a 134-year period. This level of precision is astonishing for a system developed during the 11th or 12th century CE that remained reliable for centuries afterward.

How Maya Astronomy Integrated Into Daily Life

Maya astronomical knowledge wasn't confined to priests or elites—it was woven into both everyday and ritual calendars. The Dresden Codex masterfully integrated the 260-day sacred calendar with the 365-day civil year. Lunar observations likely formed the foundation, with eclipse markers subsequently added by repurposing existing tables rather than rewriting entire sections.

These ancient scribes demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of long-term astronomical drift and developed methods to correct it. According to Earth.com reports, the surviving table likely originated around 1083 or 1116 CE. When properly applying the reset points, this system would have accurately predicted the total solar eclipse that occurred on July 11, 1991, over Mexico and Central America—some accounts mistakenly reference 1999, but historical records confirm the 1991 event.

Fragments discovered at San Bartolo, dating back to 300–200 BCE, reveal that Maya scribes maintained a centuries-long tradition of recording day counts and lunar observations. The Dresden Codex wasn't an isolated creation but rather part of an evolving system of astronomical knowledge that spanned generations.

Ancient Methods Versus Modern Technology

Contemporary astronomers can calculate solar eclipses down to the minute using advanced computer programs that incorporate Newton's laws, precise measurements of Earth's and moon's speeds and positions, and detailed orbital tilt calculations. In striking contrast, the ancient Maya achieved remarkable accuracy through tables carefully drawn in ink on fig tree bark, demonstrating their extraordinary mathematical and observational capabilities.

This thousand-year-old manuscript continues to fascinate researchers and astronomy enthusiasts alike, serving as a testament to the sophistication of ancient Mesoamerican science and its enduring relevance in understanding celestial phenomena.