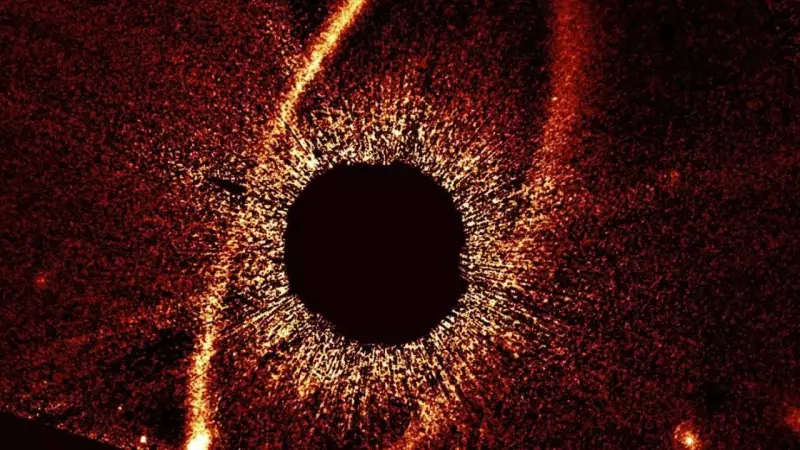

For decades, scientists believed the violent chaos of planetary birth was a brief, fiery chapter. Once planets settled into stable orbits, the era of catastrophic collisions was thought to end. However, groundbreaking observations from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope are shattering this peaceful narrative, revealing that planetary systems may remain tumultuous demolition derbies for far longer than anyone imagined.

Fomalhaut's Vanishing 'Planet' and Emerging Dust Clouds

The story unfolds around Fomalhaut, a brilliant star located a mere 25 light-years from Earth in the constellation Piscis Austrinus. This star, more massive than our Sun, is famous for its vast, dusty debris belts—a colossal version of our own solar system's Kuiper Belt. These belts are the cosmic junkyards of planetary construction, where leftover rocks and ice constantly jostle.

In 2008, Hubble made headlines by seemingly imaging an exoplanet directly, an object dubbed Fomalhaut b. Yet, in a cosmic mystery, this 'planet' gradually faded from view and had vanished completely by 2014. Astronomers now believe they witnessed not a planet, but the expanding, fading aftermath of a colossal crash.

This theory gained stunning credibility in 2023. Analysing fresh Hubble data, scientists spotted a new, sudden point of light within the same debris disk. This object, named circumstellar source 2 (cs2), appeared just two decades after the first cloud (now called cs1) and showed identical characteristics—a brightening cloud of fine debris.

Two Catastrophic Crashes Challenge 100,000-Year Theories

The appearance of two such massive dust clouds within a human lifetime has sent shockwaves through the astronomy community. Earlier models predicted that collisions between large bodies in a mature system like Fomalhaut should be exceedingly rare, happening perhaps once every 100,000 years or more.

'Observing two of these events in just 20 years is extraordinary and fundamentally changes our understanding,' the findings suggest. If such impacts were truly that rare, the probability of Hubble catching even one would be minuscule. Witnessing two implies that the Fomalhaut system is a far more active and violent construction site than models predicted.

Adding to the puzzle, both collision sites—cs1 and cs2—are located close together along the inner edge of the main debris belt. This non-random clustering hints that unseen forces, likely the gravitational pull of hidden planets, are shepherding these ancient planetesimals into specific traffic lanes, dramatically increasing their odds of a catastrophic pile-up.

Fomalhaut: A Laboratory for Our Solar System's Violent Past

By studying the expanding debris clouds, astronomers have estimated the size of the colliding bodies. The data suggests the objects were roughly 60 kilometres in diameter—comparable to some of the largest asteroids in our own solar system, like Hygiea or Sylvia.

This discovery transforms the Fomalhaut system into a unique natural laboratory. Scientists now estimate that hundreds of millions of similar planetesimals could be orbiting the star, providing endless opportunities for collision-driven research. These violent events are not merely destructive; they are crucial architects of planetary systems.

Planetesimal collisions play a vital role in planetary development by:

- Grinding down material and redistributing elements.

- Transporting volatile components like water ice from the outer to the inner regions of a star system.

- Potentially delivering the very ingredients that made Earth a habitable world.

The chaotic scenes Hubble has captured around Fomalhaut are likely a direct window into the frenzied adolescence of our own solar system. The giant impacts that formed our Moon, the late heavy bombardment that scarred our inner planets—all were part of this extended era of cosmic violence that, as Hubble proves, may last much longer than the textbooks stated.