The draft ward reservation matrix released for the upcoming elections to Bengaluru's newly carved city corporations has ignited controversy by revealing a significant shortfall in women's representation. None of the five corporations have achieved the 50% benchmark, a long-standing political and policy commitment in Karnataka's urban governance framework.

Analyzing the Numbers: A Clear Deficit

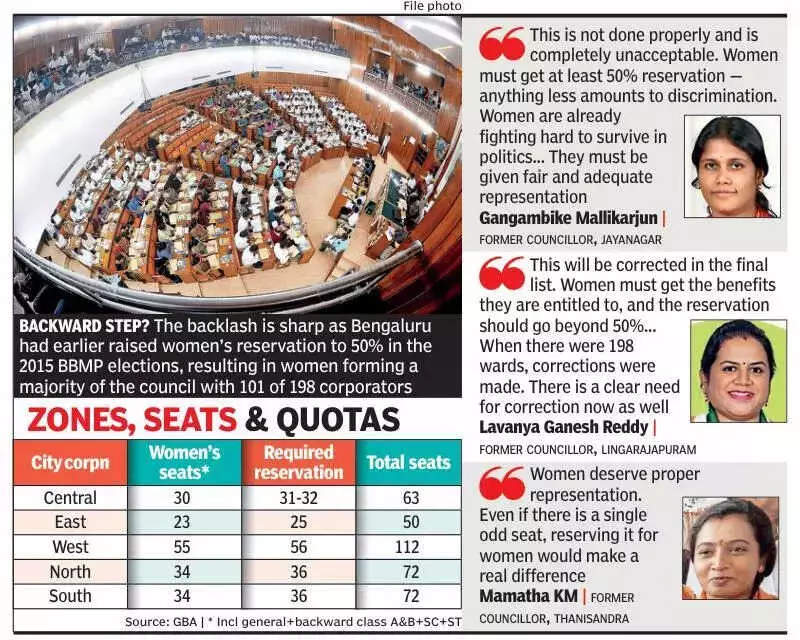

An in-depth analysis of the draft reservation list shows that only 176 out of the total 369 wards—approximately 47.7%—are reserved for women. This falls nine seats short of the mandated 50% benchmark. Former women councillors and rights advocates argue that this deficit is not merely incidental but signals a deliberate dilution of commitment to women's reservation during the transition to the new governance structure under the Greater Bengaluru Authority (GBA).

Zone-Wise Disparities Highlight the Issue

The disparities are particularly visible across different zones within the city. The East zone is the most affected, with just 23 out of 50 wards (46%) reserved for women. The Central zone follows closely, with 30 out of 63 wards (47.6%) allocated for women. Even zones with larger councils fail to meet the benchmark. The West zone, the largest with 112 wards, reserved only 55 seats (49.1%), while both the North and South zones, each with 72 wards, allotted just 34 seats apiece (47.2%).

Official Justification and Public Backlash

Nandakumar B, undersecretary to the government, defended the reservation framework, stating it was prepared in accordance with the Greater Bengaluru Governance Act, 2024, using Census 2011 population data. He clarified, "Across all categories, including unreserved wards, 50% of the seats are earmarked for women. However, where the number of wards in a category is an odd number or limited to one, the lone ward or the final ward will not be reserved for women."

Despite this explanation, the draft reservation list has faced substantial public opposition. More than 700 objections were submitted to the urban development department (UDD), with a large majority specifically addressing the issue of women's reservation. Nandakumar told TOI, "Once all the objections are in, we will look into the issue and see what changes are needed."

Criticism Over Administrative Feasibility

What has drawn sharper criticism is that several corporations have even-numbered councils, where achieving the 50% mark would have been administratively straightforward. Shwetha HR, former councillor from Doddanekundi, pointed out, "In a 72-member council, there is no justification for stopping at 34 women's seats when 36 is mathematically feasible."

Kathyayini Chamaraj, executive trustee of Civic-Bangalore, added, "If, after reserving seats, there are seven fewer seats for women than the required 50%, the exception made that the leftover unreserved seats cannot be reserved for women goes against the law. The required number of seats for women to fulfil 50% should be made up by reserving whatever seats are left over for women."

Historical Context and Higher Expectations

The backlash is particularly strong because Bengaluru had previously set a higher bar for women's political representation. In the 2015 elections to the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike, women's reservation was raised from 33% (in 2010) to 50% for the first time. Of the 198 wards then, 99 were reserved for women, and with women candidates also winning from unreserved wards, the final council comprised 101 women corporators—51% of the total strength.

This historical precedent makes the current shortfall even more glaring and raises questions about the commitment to gender parity in the city's evolving governance model. The ongoing debate underscores the need for transparent and equitable reservation policies as Bengaluru transitions to its new administrative framework.