Kerala Government Leases Wetland to Private Society Despite Strong Objections

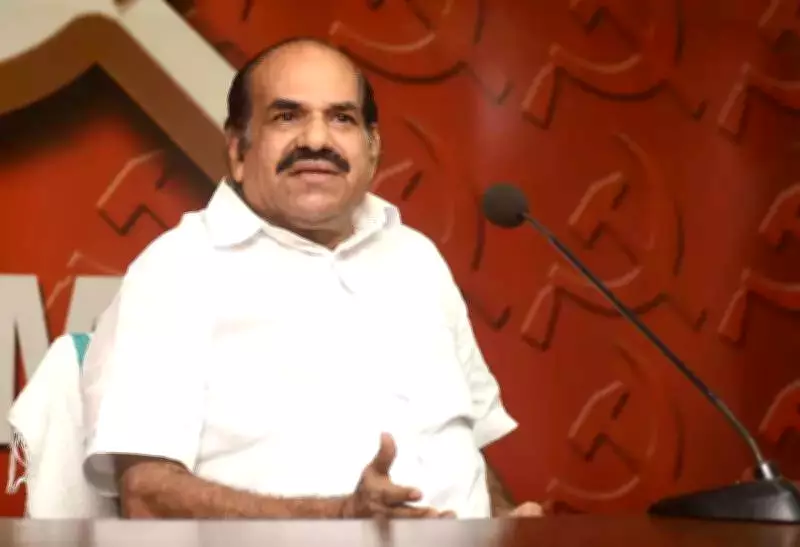

In a controversial move, the Kerala government has leased a marshy stretch of government land in Thalassery, officially recorded as wetland and historically tied to public drinking water infrastructure, to a private memorial society named after former CPM leader Kodiyeri Balakrishnan for a period of 30 years. The decision, publicly announced on January 14, has sparked significant debate over its legality, environmental impact, and public interest implications.

Details of the Lease Agreement

The government order issued on January 19 formalized the Cabinet decision taken on January 14, approving the lease of 1.139 acres (0.4613 hectares) of land in Ward 2 of Thalassery municipality to the Kodiyeri Balakrishnan Memorial Academy of Social Sciences (KBMASS). The society plans to establish a research center on the site at a nominal lease rent of just Rs 100 per year.

While the post-Cabinet press note and subsequent media reports portrayed the allotment as a routine procedure for a public-purpose institution, internal government records and Cabinet notes reveal a more complex and contentious process. The official file indicates that the land is government puramboke vested with the Kerala Water Authority (KWA) and is traversed by a permanent water channel—critical facts that triggered sustained objections within the government but were not disclosed to the public.

Environmental and Legal Objections Overridden

Revenue documents confirm that a stream passes through 0.044 hectares of the site, and the land previously housed a KWA office, a pump house, and water storage facilities built as part of the Thalassery drinking water expansion project. The land revenue commissioner's report notes the strategic location of the land, lying barely 100 meters from the Thalassery–Kannur National Highway and immediately east of the KSRTC bus stand, underscoring its public utility value.

The local self-government department categorically objected to the lease, stating in its note that water channels are ‘inviolable’ and cannot be assigned to private entities. The law department, citing Supreme Court rulings, warned that even if a water body appears dry, it cannot be alienated or fragmented. It also pointed out that no denotification was issued under the Kerala Municipality Act to transfer vesting rights away from the municipality.

These objections are explicitly listed among the references in the final order but were not reflected in the outcome. The KWA also raised concerns, informing the government that the land was required for its operational needs and that water storage structures and pump houses constructed for the Thalassery drinking water augmentation scheme were in the vicinity.

Valuation and Public Loss Concerns

One of the sharpest red flags in the file relates to valuation and public loss. Since the land is government puramboke, no official fair value exists. However, using comparable private land in the neighbouring survey block, officials assessed the land value at Rs 11,61,600 per acre, placing the total value of the 0.4613 hectares at Rs 5.35 crore. The order itself records this figure, highlighting the significant financial implications of the nominal lease.

The justification for invoking special powers under Rule 21(ii) of the 1995 Land Assignment Rules—meant to be used only in cases of overriding public interest—was questioned internally. The law department noted that leasing wetland and water body-linked land to a private charitable society, even one proposing academic activity, does not automatically qualify as overriding public interest, especially when weighed against drinking water requirements and future urban needs.

The revenue secretary suggested exploring alternative sites, but the proposal proceeded without such an exercise, further fueling criticism.

Environmental and Political Criticism

The decision has drawn sharp criticism from environmental voices, who see an unsettling political continuity rather than an aberration. Noted environmentalist Sridhar Radhakrishnan commented, "This is no different from what happened during the final phase of the Oommen Chandy government, when wetlands were indiscriminately filled up and cleared for projects—decisions that even the Left parties described as reckless."

He added, "What is striking is that the same opposition, after coming to power, appointed committees to reverse those decisions. Today, however, the government's actions are not even marginally different from what it once attacked so fiercely."

The controversy raises fresh questions about the legality, public interest, and environmental safeguards in government land allocation processes, particularly in ecologically sensitive areas like wetlands.