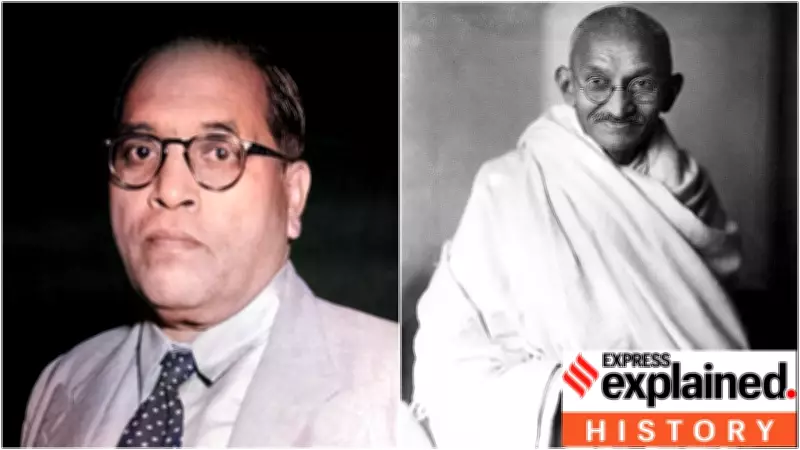

The Enduring Conflict: Gandhi and Ambedkar's Foundational Disagreements

The intellectual and ideological battle between Mahatma Gandhi and B.R. Ambedkar represents one of the most significant debates in modern Indian history. Seventy-eight years after Gandhi's death, their profound disagreements continue to resonate through India's political and social landscape. As scholar Arundhati Roy observed in The Doctor and the Saint, this was far more than a personal disagreement—it was a clash between two distinct visions for India's future, each representing separate interest groups within the national movement.

The Political Representation Divide

The first major confrontation between Gandhi and Ambedkar occurred in 1931, just weeks before the Second Round Table Conference in London. Their meeting in Bombay revealed fundamentally different perspectives on political representation and national identity. When Gandhi questioned Ambedkar's criticism of the Congress, interpreting it as an attack on the homeland, Ambedkar delivered his famous response: "Gandhiji, I have no homeland... No Untouchable worth the name will be proud of this land."

This tension reached its climax at the London conference, where Gandhi declared he personally represented all Untouchables, while Ambedkar insisted that only those who shared the identity of the Depressed Classes could truly advocate for their justice. The central issue became separate electorates—Ambedkar viewed them as essential for political rights, while Gandhi believed they would fracture Hindu society. The conflict intensified in 1932 when British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald granted separate electorates, prompting Gandhi's dramatic fast-unto-death protest from Yerawada Central Jail.

Contrasting Views on Religion and Reform

Their religious perspectives revealed another deep chasm. Gandhi approached Hinduism as a reformable tradition, using reinterpretation of texts like the Bhagavad Gita to advocate for social change. As scholar Bindu Puri notes, Gandhi transformed concepts like yajna from ritual sacrifice to selfless service, believing social reform could occur within religious frameworks.

Ambedkar, however, saw Hinduism as fundamentally irredeemable. His famous 1935 declaration—"I was born a Hindu but I will not die a Hindu"—encapsulated his belief that caste discrimination was intrinsic to the religion. Despite his disillusionment, Ambedkar recognized the human need for spiritual belonging, leading to his eventual conversion to Buddhism in 1956 after extensive study of various faiths.

Divergent Concepts of Justice

The two leaders approached justice through completely different philosophical frameworks. Gandhi emphasized moral transformation alongside institutional change, drawing from Indian ethical traditions to advocate for samata (equality), samabhava (equanimity), and samadarshita (equal vision). He believed justice required both representation in legislatures and a "change of heart" among oppressors.

Ambedkar, in contrast, focused primarily on institutional mechanisms—laws, rights, and constitutional safeguards capable of restraining power and correcting systemic injustice. He insisted that justice could not rely solely on moral feelings or individual conscience, requiring robust legal frameworks to protect marginalized communities.

These foundational disagreements between Gandhi and Ambedkar continue to shape contemporary debates about representation, social justice, and India's constitutional democracy, making their historical clash profoundly relevant to current political discourse.