The launch of the Akali Movement in the early 20th century was not merely a religious reform effort but a clear signal of open rebellion against British colonial authority in India. This bold assertion was made by a prominent scholar, shedding new light on a crucial chapter in the nation's fight for independence.

The Scholar's Perspective on a Defining Struggle

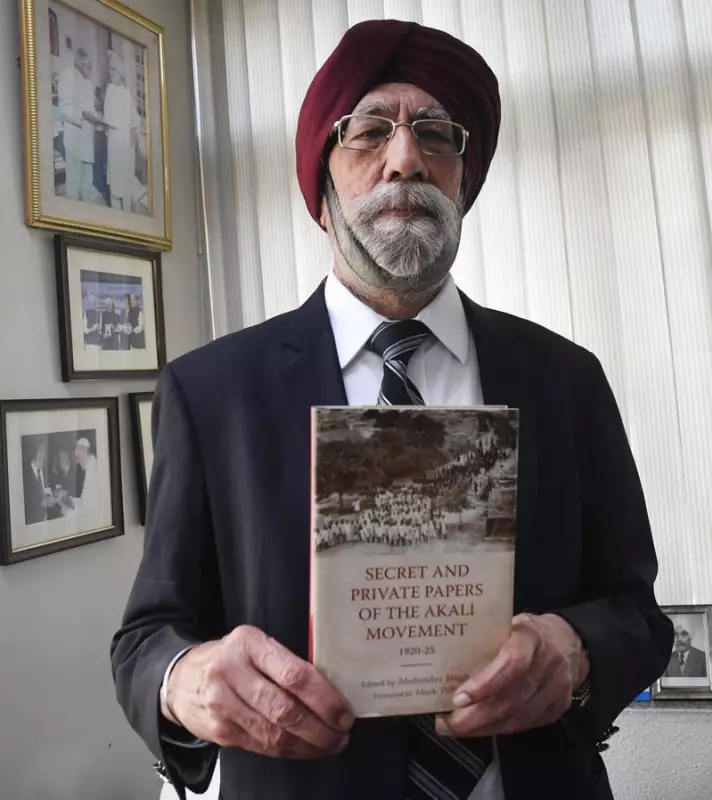

Speaking at a seminar titled 'Contribution of Sikhs in the Freedom Struggle' at Delhi University, Dr. Balwant Singh Dhillon, a former professor of Guru Nanak Studies, presented a compelling analysis. He argued that the British authorities immediately recognized the Akali Movement's true nature as a direct political challenge to their rule, not just a campaign for Sikh religious autonomy.

The movement, which formally began around 1920, is often associated with the Gurdwara Reform Movement aimed at liberating Sikh shrines from corrupt hereditary custodians, known as Mahants. However, Dr. Dhillon emphasized that its implications were far broader. The British, he noted, were acutely aware that the movement's drive for self-governance within religious institutions posed a fundamental threat to their overarching political control.

British Crackdown and Martyrdoms

The colonial response was swift and severe, confirming the movement's perceived threat. Dr. Dhillon highlighted the Nankana Sahib massacre of February 1921 as a pivotal and bloody event. In this tragedy, more than 130 peaceful Akali protesters were killed by the hired guards of the Mahant, with alleged British complicity. This event galvanized the movement and exposed the brutal lengths to which the establishment would go.

Further evidence of the rebellion's intensity is found in the over 400 Sikhs who were sentenced to death during the movement's course. Additionally, more than 2,000 received life imprisonment, and a staggering 30,000 were imprisoned for varying terms. These numbers, according to the scholar, underscore the scale of the confrontation and the British determination to crush it.

A Foundation for Broader Nationalism

Dr. Dhillon's analysis connects the Akali struggle directly to the larger Indian freedom movement. He pointed out that the movement's leaders and participants were deeply influenced by and integrated with the wider nationalist campaign. The seminar itself was organized by the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) and Delhi University's history department, reflecting the academic recognition of this link.

The scholar detailed how the British attempt to create a separate "Sikh identity" for political management backfired. The Akali Movement, while rooted in Sikh religious consciousness, evolved into a powerful force against colonialism. Its methods of peaceful protest, mobilization, and sacrifice provided a template and inspiration for other groups across India.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 was cited as a critical catalyst that radicalized the Sikh community and many others, paving the way for movements like the Akalis to take a more defiant stand. The movement's legacy, therefore, is not confined to Sikh history but is firmly embedded in the narrative of India's collective journey to overthrow colonial rule.

In conclusion, the Akali Movement stands re-examined through this scholarly lens not as an isolated religious event, but as a decisive and openly rebellious front in India's war for independence. Its suppression by the British state, marked by extreme violence and mass incarcerations, is a testament to its powerful challenge to colonial authority. The movement's spirit and sacrifices contributed significantly to the national awakening that eventually led to India's freedom in 1947.