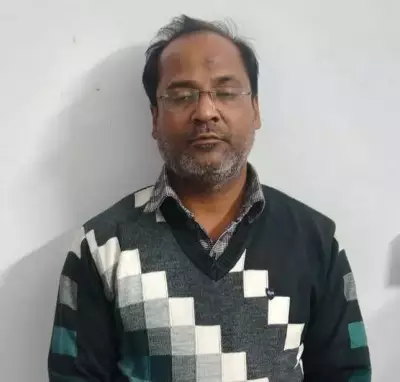

Political strategist and futurist Vimal Singh has provided a deep analysis of the ongoing churn in South Asia, arguing that it represents a fundamental structural realignment far beyond simple election math or isolated border skirmishes. In this shifting landscape, Bangladesh has emerged as a critical node, facing immense pressure while India exercises strategic restraint.

The Multifaceted Pressure on Bangladesh

Singh outlines that Bangladesh is currently squeezed from multiple directions. Internally, the nation grapples with severe political polarisation and significant economic stress. Externally, its relationship with India is undergoing a careful recalibration. Adding to the complexity are persistent concerns regarding the safety of minority communities within its borders.

Unlike some of its neighbours, Bangladesh retains a degree of institutional elasticity, according to Singh. However, he cautions that this flexibility alone does not automatically confer leadership capability. This precise gap, he suggests, is where the limitations of looking to Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus for political salvation become starkly evident.

Yunus: A Moral Voice, Not a Political Solution

While acknowledging Yunus's global stature as a respected economist and moral authority, Singh warns against projecting him as a direct political fix. "Yunus represents an alternative model of thought, not governance," he states. His international credibility and reformist economic ideas, though influential abroad, clash with the hard-edged, volatile nature of Bangladesh's domestic politics, which is neither technocratic nor driven by consensus.

"Yunus may embody reformist economics and moral persuasion, but he lacks the political crisis-handling instincts required to navigate Bangladesh's volatile political ecosystem," Singh explains. The analyst emphasises that the country's challenges demand political acumen that goes beyond moral suasion.

India's Strategy of Calibrated Restraint

When examining India's role, Singh endorses New Delhi's policy of measured response. He cites India's reaction to incidents of violence against minorities in Bangladesh as a prime example. Instead of overt escalation, India opted for calibrated restraint, leveraging the power of public opinion, civil society pressure, and undeniable economic realities to shape outcomes.

This approach, Singh argues, has revealed a critical miscalculation within certain quarters in Bangladesh. The assumption that Indian Muslims could be mobilised against India's interests based on religious solidarity has collapsed. Indian Muslims have not aligned with any external agenda, dealing a psychological blow to strategies banking on cross-border religious leverage.

The result is a stark reality check for Bangladesh: radical slogans do not create jobs, attract investment, or ensure stability. The nation's employment, industry, and growth prospects remain deeply interlinked with stable ties to India. As economic pressures increase, public sentiment is shifting, with many recalling more stable periods in the bilateral relationship.

Singh points to a strategic opening that lies not in importing divisive politics but in re-engaging with the Bengali-speaking Hindu electorate, a group that increasingly feels politically marginalised. A focus on cultural and civilisational alignment, rather than short-term identity politics, could significantly alter the political trajectory.

In conclusion, Vimal Singh posits that Bangladesh stands at a decisive crossroads. Muhammad Yunus symbolises possibility and a reminder that modern legitimacy stems from trust, not coercion. Meanwhile, India's quiet but firm diplomacy has already altered ground realities, creating ripple effects felt from Dhaka to Kolkata, setting the stage for the next phase of South Asia's geopolitical evolution.