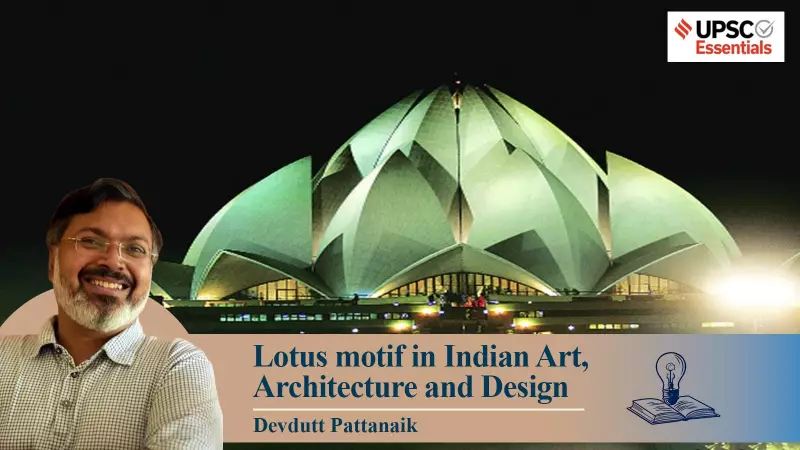

The lotus flower, while adopted as a symbol by a major political party in contemporary India, holds a heritage that spans millennia, deeply embedded in the nation's myths, rituals, and artistic expressions. From simple rice flour drawings in villages to grand architectural marvels, this sacred symbol continues to invite introspection into the deeper springs of life. Renowned mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik explores this enduring legacy.

From Ashokan Pillars to Temple Spires: An Architectural Journey

Interestingly, the lotus is absent from Harappan art. Its formal entry into the subcontinent's visual language occurred in the 3rd century BCE with the rise of the Mauryan Empire. The polished sandstone Ashokan pillars, each carved from a single block, were crowned with lotus capitals. This flower base supported sculptures of lions, bulls, elephants, and horses, marking the lotus's inaugural role in Indian statecraft and royal proclamation.

The narrative continued in Buddhist monuments between 100 BCE and 100 CE. Stupas at sites like Sanchi, Bharhut, and Amravati featured lotus medallions on railings. Their reliefs depicted lotus ponds and yakshas, with the earliest known image of Goddess Lakshmi seated on a lotus appearing here. This imagery transcended traditions, with Bodhisattvas, Tara, and the Jain goddess Padmavati all associated with the lotus.

By 500 CE, Hindu temple architecture integrated the lotus into its core design. Temple plans often followed lotus diagrams. The Sun Temple in Modhera, Gujarat, exemplifies this, with its platform rising like giant petals lifting the sanctum skyward. Pillar capitals bloomed, ceilings were designed as inverted lotuses, and outer walls displayed deities holding lotus buds. The cosmic symbolism extended to the domes and towers of sites like Angkor Wat and Hampi, evoking the cosmic lotus of Mount Meru.

Adaptation and Evolution in Indo-Islamic and Sikh Traditions

With the advent of Indo-Islamic architecture after the thirteenth century, the lotus seamlessly adapted to a new aesthetic focused on geometry. Domes took the shape of lotus buds, with carved petals at their base and inverted lotus forms at the top, as seen in Humayun's Tomb and the Taj Mahal. Lotus buds lined arches, a feature first seen in the Alai Darwaza, and the motif adorned balconies, walls, and floors through intricate inlay work. Gardens were designed for lotuses, and even Akbar's throne in Fatehpur Sikri rested on a lotus base.

Sikh architecture embraced the symbol with equal reverence. The dome of the Golden Temple in Amritsar evokes a half-open lotus, and lotus patterns grace its gates and windows. The Guru Granth Sahib employs the flower as a metaphor for a mind untouched by worldly desire, echoing ancient Upanishadic thought.

The Lotus in Body, Art, and Modern Marvels

In tantric geometry, the lotus transforms into a cosmic diagram. Interlocking shapes create eight-petalled or six-petalled lotuses, each representing the womb of creation. This symbolism extends to human anatomy, where texts map seven principal chakras as lotuses along the spine, from a four-petalled base to a thousand-petalled crown.

Performing and textile arts also celebrate the motif. Dance manuals describe lotus mudras, while yogic postures like padmasana aim to transform the body into a lotus for meditation. In textiles, a 16th-century silk panel from eastern India showcases concentric lotus petals. Regional embroidery styles—Phulkari of Punjab, Kantha of Bengal, Ikat of Odisha, Kasuti of Karnataka, and Paithani of Maharashtra—all place the lotus at the heart of their designs.

Modern India continues this tradition. The Bahai House of Worship in Delhi, completed in 1986, is shaped as a half-open lotus with twenty-seven marble petals. Its nine entrances open to a central hall, embodying the flower's ancient associations with purity, inclusion, and universal welcome.

Across centuries, from prehistoric cave art to contemporary architecture, the lotus remains India's simplest yet most profound symbol. It persistently encourages every generation to look beyond the surface and seek the hidden, eternal source from which all life unfolds.