Kolkata Wrote Her Own History, One Year at a Time

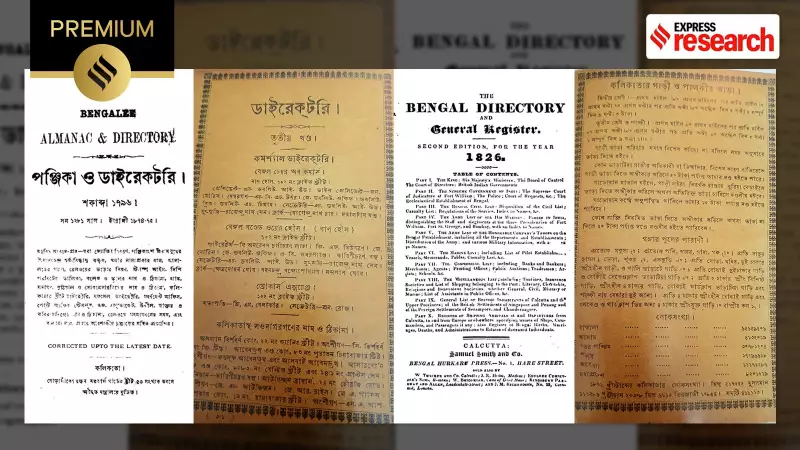

Nineteenth-century Kolkata quietly documented her own transformation through annual publications. While colonial government reports provided a stark outline of the city, English directories and vernacular almanacks captured the vibrant rhythms of urban life with remarkable precision. These humble volumes, published at the start of each Gregorian and Hindu calendar year, became instruments of annual self-reckoning for the growing metropolis.

The Official Record Versus the People's Archive

Most chronicles of 18th and 19th-century Kolkata emerged from colonial dispatches, government reports, and official gazettes. These documents spoke with the iron voice of the state, rendering the city in broad administrative strokes. Yet Kolkata was not born of decrees alone. To understand how the city actually lived, breathed, and evolved, one must turn to more accessible companions: the annual directories and almanacks that ordinary citizens used daily.

Two publications stood out for their meticulous record-keeping. Thacker's Indian Directory, first issued in 1864, began as a regional guide to the Bengal Presidency. By 1885, it expanded across the subcontinent, publishing annually until 1960. Meanwhile, Samuel Smith & Co.'s Bengal Directory and Annual Register appeared even earlier, running from 1825 until the end of the Great Revolt in 1858-59. These were often printed at the Bengal Hurkaru Press near Tank Square, today's BBD Bagh area.

A City Revealed in Annual Snapshots

These directories were comprehensive. They listed European residents and prominent Indians, government departments, schools, foreign consulates, mills, clubs, hotels, and hospitals. They detailed railway lines, shipping services, telegraph offices, postal routes, trade associations, learned societies, and newspapers. Nothing escaped their enumeration.

Most importantly, they documented city streets with astonishing detail. Each volume grew dramatically, from initial 400-page editions to nearly 2,000 pages by their final publications. House by house, lane by lane, Kolkata emerged not as an abstraction but as a tangible, sequential journal. A name disappearing from Cossaitollah Gully one year and reappearing on Chowringhee the next traced the city's quiet mobility and repositioning.

Mapping Urban Transformation

The directories captured Kolkata's physical evolution with precision. They recorded how Cossaitollah transformed into Bentinck Street around 1876. They documented the construction of Harrison Road, now Mahatma Gandhi Road, connecting Howrah and Sealdah railway stations between 1889 and 1892. They described the chaos when Central Avenue, now Chittaranjan Avenue, was built in the early 20th century.

Consider 5 Chowringhee, now JL Nehru Road. Today it houses a modern multiplex, but the directories reveal its layered history:

- Between 1870-1873, soldier of fortune Percy Wyndham occupied the premises

- By 1897, Whiteaway, Laidlaw and Company occupied numbers 4, 5, 6, and 7

- In 1918, William Leslie and Company operated on the ground floor

- By 1931, The Statesman newspaper expanded into the building

- In 1935, the structure was demolished for the Art Deco Metro Cinema

Only these annual directories could provide such detailed locational interplay across decades.

The Social and Economic Landscape

These volumes documented more than addresses. They captured social hierarchy, with Europeans foregrounded and Indians subtly qualified as "prominent." Yet within their typographical order flowed an undercurrent of change. Lawyers, doctors, contractors, printers, and hotel-keepers of Indian origin began appearing, their addresses shifting southward and eastward as new neighborhoods formed.

Economically, the directories read like inventories of ambition. Carvers and gilders stood shoulder to shoulder with boarding houses, chop shops, confectioners, shipping firms, and auctioneers at Tiretta Bazar, Radha Bazar, Bowbazar, College Street and Clive Street. They documented Kolkata's transition from an agrarian to commercial economy with precision no official report could match.

The Vernacular Companion: Panjikas as Urban Archives

While English directories mapped colonial modernity, Bengali Panjikas mapped domestic continuity in the language of faith and tradition. These almanacks, traditionally astrological and ritualistic, evolved during the late nineteenth century under the subtle influence of English street directories.

P. M. Bagchi's Directory & Panjika, established in 1883-84, stands as a prime example. Alongside tables of eclipses, auspicious hours, and festival days, it tucked in lists of residents and tradesmen. A priest would use it to determine wedding hours, a householder to check addresses, and a trader to locate market rates. Sacred and civic concerns shared the same pages.

In these hybrid volumes, indigenous society negotiated modernity without abandoning tradition. Advertisements for schools and patent medicines jostled with religious calendars. Municipal notices hovered near ritualistic Ekadashi fasting prescriptions. Commerce and cosmology became strange but harmonious neighbors.

Richness Overlooked, History Rediscovered

Despite their richness, these sources occupy the margins of public memory. Libraries once dismissed them as ephemeral, useful for a single year before replacement. Language created another barrier—Thacker's spoke to the anglicized, Panjikas to the vernacular. Historiography rarely built bridges between them.

Yet within their yellowed pages hums Kolkata's forgotten heartbeat. They reveal Butto Kristo Paul operating a chemist shop in Chitpore-Hatkhola-Shovabazar, supplying European-style medicines alongside local herbal remedies. They show indigenous tailors like De, Das & Company making both dhotis and pantaloons, their advertisements infused with aspiration.

Kolkata reported her transformation quietly, year by year, through these annual publications. They were once indispensable tools—address books, city guides, professional directories, and tariff handbooks rolled into one. Today, they offer historians and social anthropologists a treasure trove of urban aspiration, mobility, and identity. The city wrote herself every year, and we must only learn to read her script.