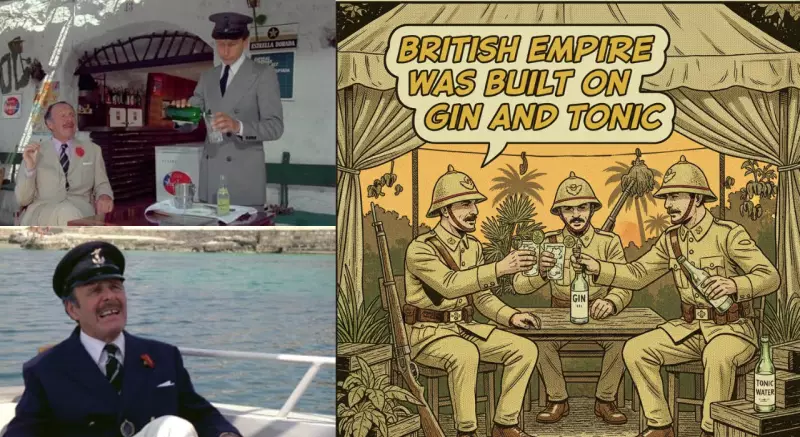

A short video clip circulating on Instagram, often paired with gin brand labels and captions about empire, has sparked fresh interest in a surprising historical truth. It features a stiff-backed British aristocrat on a yacht, his Mediterranean leisure shattered by a domestic crisis: the ship has run out of tonic water. This moment, lifted from the 1975 British-Spanish comedy Spanish Fly, reveals that the iconic gin and tonic was once a crucial tool of imperial survival, not merely a refreshing cocktail.

The Viral Monologue and Its True Origins

The character is Sir Percy de Courcy, played by the actor Terry-Thomas. In the scene, upon hearing his manservant Perkins apologise for the lack of tonic, Sir Percy launches into an impassioned rant. "Do you realise that gin and tonic is the cornerstone of the British Empire? The Empire was built on gin and tonic," he declares. He explains its dual purpose: "Gin to fight the boredom of exile, and quinine to fight malaria." This clip is often shared online, mistakenly attributed to figures like Winston Churchill or old Schweppes ads, but its core message is historically accurate.

Quinine: The Bitter Medicine That Made Empire Possible

For European empires, especially the British, malaria was a deadlier enemy than any opposing army in tropical climates. In postings like India, Africa, and Southeast Asia, disease often claimed more lives than combat. The solution, discovered long before germ theory, was quinine. This compound, extracted from the bark of the South American cinchona tree, was known for centuries as "Jesuit's bark" and was the only effective anti-malarial prophylactic.

By the 19th century, the British military routinely issued quinine to soldiers and administrators stationed overseas. The major hurdle was its intense bitterness. To make it palatable for daily consumption, it was mixed with water, sugar, and carbonation, creating the earliest form of tonic water. Commercial production soon followed, with brands like Schweppes marketing "Indian Quinine Tonic" explicitly for colonial use. This was fundamentally medicine, not a leisure drink.

Gin's Practical Role in Colonial Survival

Gin entered the equation for starkly practical reasons. By the 1800s, it was cheap, widely available, and part of standard military rations. Adding gin to the bitter quinine tonic masked its taste, ensuring that officials and soldiers actually consumed their daily dose. What began as an improvised medical necessity quickly became a ritual—the sundown "dose" to ward off fever.

British military doctors further enhanced the mixture by adding lime or lemon peel, which helped prevent scurvy, a disease caused by vitamin C deficiency. Thus, a single daily drink addressed multiple threats: quinine fought malaria, citrus prevented scurvy, and alcohol made the regimen tolerable while combating boredom. This concoction was measured, issued, and consumed as a critical part of life in the tropics, long before it graced cocktail menus.

Medicine Before Myth: A Pillar of Imperial Durability

At the height of the British Empire, quinine was as essential as gunpowder. It did not cause imperial expansion, but it made sustained occupation survivable. The gin and tonic that emerged from this need was a pragmatic response to a lethal environment. The association was so well-established that Winston Churchill later remarked, not entirely in jest, that gin and tonic had "saved more English lives, and minds, than all the doctors in the Empire."

The enduring legacy of this history is clear. While Britain did not conquer its colonies with a cocktail glass in hand, in malarial regions, the empire likely could not have been maintained without the protective shield of quinine—and the gin that made swallowing it possible. The viral clip of Sir Percy de Courcy, therefore, is more than a comedy bit; it's a simplified echo of a vast medical and colonial history that shaped the modern world.