Ancient Shell Horns Rediscovered in Spain Reveal Neolithic Communication Network

Archaeologists working in Spain have achieved something remarkable. They have successfully played ancient shells that date back approximately 6,000 years. These instruments, crafted from large marine snail shells, were discovered at various prehistoric sites across Catalonia. When played, they produced strong, stable notes. Researchers believe these sounds were loud enough to travel across valleys and penetrate underground spaces. This discovery hints at an early system of long-distance communication used by Neolithic communities.

Shell Horns Were High-Powered Sound Tools, Not Simple Ornaments

The findings, published in the journal Antiquity, challenge previous assumptions. These shell horns were not mere decorative items or ritual objects. Instead, they appear to have been designed as powerful acoustic tools. Early farming communities likely used them to send signals across landscapes where visibility was poor. The horns could have helped people coordinate activities or warn of dangers over considerable distances.

Ancient shells that still produce thunderous sound

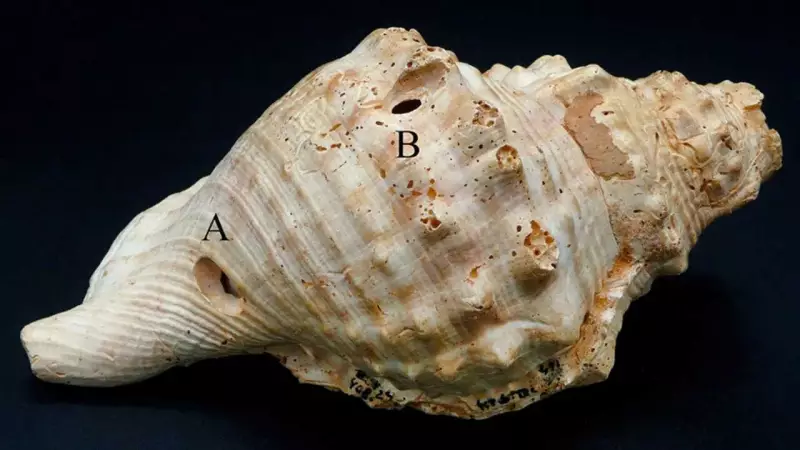

The horns were made from a specific type of large Mediterranean sea snail known as Charonia lampas. The natural shape of this shell makes it ideal for producing resonant sound when modified. Researchers examined twelve shell horns recovered from five archaeological sites clustered in the Llobregat River basin. This region is known for dense Neolithic settlement and activity.

Despite being thousands of years old, eight of these instruments remained acoustically functional. During tests, the best-preserved shells produced tones exceeding 100 decibels. One shell even reached about 111.5 decibels when measured from one metre away. This sound level is comparable to a car horn or a brass instrument. It is intense enough to be heard over long distances outdoors.

Horns Found Across Villages, Caves, and Underground Mines

One of the most striking aspects of this discovery is the variety of locations where the horns were found. The shell instruments appeared in multiple Neolithic contexts. These included open-air farming settlements, a high-altitude cave site overlooking steep valleys, and mine galleries used for extracting variscite. Variscite is a prized green mineral that was used in ornaments.

The sites are all located within roughly a ten-kilometre radius along the river corridor. This geographical clustering indicates the horns were part of a shared local tradition. They were not isolated, one-off objects. Their repeated appearance across multiple locations suggests they served a practical function. Communities spread across the same region would have understood and used these instruments.

How Neolithic People Turned Seashells into Signal Horns

Prehistoric craftspeople transformed marine shells into playable horns through specific modifications. They removed the shell's apex to create a mouthpiece. In many cases, this opening was about twenty millimetres wide. Researchers note this size tends to produce a stable pitch and consistent tone.

The shells also showed signs of natural wear caused by marine organisms. This included sponge boreholes and worm-like markings. This detail suggests the shells were likely collected after the animals had died. They may have been chosen specifically for their acoustic properties rather than harvested for food.

Some of the horns contained small perforations. These holes may have been used for attaching straps or cords. This would have made the instruments easier to carry during work or travel.

More Than One Note, and Possibly Primitive Melodies

Shell horns are often imagined as blunt, one-note instruments. However, the tests revealed more flexibility than expected. Some horns were able to produce up to three distinct notes. These included tones an octave and a fifth above the base note.

The instruments also produced harmonic series that match the behaviour of conical wind instruments. This means the sound was structured and repeatable. It was not random noise. The horns were played and tested under controlled conditions by an archaeologist who is also a professional trumpet player. This allowed researchers to measure both the physical performance and acoustic output in detail.

A Prehistoric Communication System in Plain Sight

The core idea behind the study is simple. Sound can travel where sight cannot. In areas shaped by river corridors, valleys, cliffs, and forested terrain, long-distance signalling would have been extremely valuable. Researchers propose these horns may have helped early communities coordinate activity, warn others of danger, or maintain contact between dispersed groups working in different areas.

The fact that shell horns were recovered from underground mining sites adds another layer to the theory. Neolithic mines were dark, confined, and echoing spaces. Voice communication would have been difficult, and visibility would have been minimal. A loud horn signal could have served as an effective warning system or coordination tool in tunnels where other forms of communication were limited.

Why This Discovery Changes How We View Neolithic Life

The Neolithic period is often framed through the lens of farming, pottery, and settlement building. But these instruments hint at something more complex. If early communities were developing sound-based signalling traditions, it suggests a need for coordination and planning that goes beyond what many people imagine for that era.

It also challenges the assumption that prehistoric wind instruments were mainly ceremonial. These shells appear carefully modified for acoustic performance. They are found repeatedly in practical landscapes where communication would have mattered greatly.

A Technology That Vanished Without Explanation

One of the biggest mysteries raised by the research concerns what happened next. The shell horns appear in multiple Neolithic phases, but their presence seems to end abruptly around 3600 BC. Later layers from the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age in the same region have not produced comparable finds.

Researchers cannot yet say why the tradition disappeared. It may have been replaced by other communication methods. Shifts in settlement patterns or changing cultural practices could also be factors. For now, the archaeological record does not provide a clear answer.

The Sound of 6,000 Years Ago Returns

What makes these shell horns so compelling is their ability to connect us directly to the past. They do not just represent history visually; they bring it back in sound. The instruments still resonate with tones powerful enough to travel across landscapes. They offer a rare glimpse into how people may have coordinated and connected long before written language or modern technology existed.

For researchers, reviving these prehistoric acoustic tools is more than a novelty. It is a powerful reminder. Even 6,000 years ago, humans were already engineering creative solutions to a timeless challenge: how to communicate across distance.