More than thirteen years after receiving official sanction, a proposed railway line connecting Whitefield in Bengaluru to Kolar district has made virtually no headway, stuck at the very first hurdle of land acquisition. The project, which was approved in the 2011-12 financial year, remains a stark example of infrastructural delays plaguing Karnataka.

A Project in Perpetual Limbo

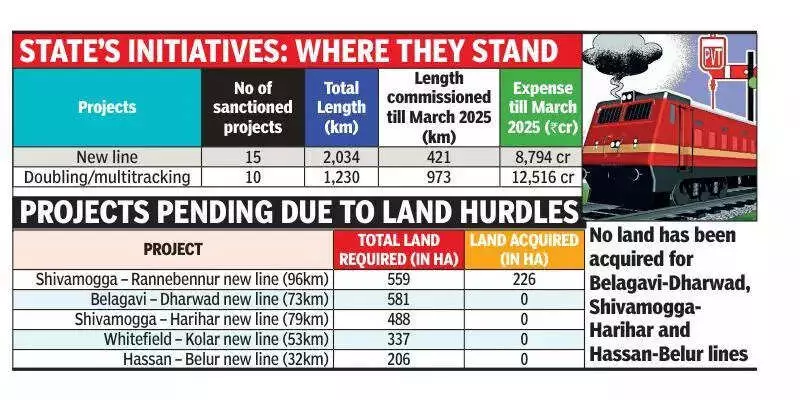

The 53-kilometre Whitefield-Kolar new line was initially conceived as a strategic link. Its primary objectives were to provide a direct connection between Bengaluru and Kolar districts and to eliminate the need for locomotive reversal at Bangarpet, thereby improving operational efficiency. The project's approval under the former UPA government was contingent on a clear agreement: the Karnataka state government would provide 337 hectares of land free of cost and bear 50% of the construction expenses.

However, data recently confirmed by the railway ministry reveals a shocking lack of progress. Not a single hectare of the required 337 hectares has been acquired to date. This prolonged inaction has occurred alongside rapid real estate development along the proposed corridor, transforming the landscape and turning land acquisition into a significantly more complex and expensive challenge.

Expert Skepticism and Soaring Costs

Railway experts now question the very feasibility of pursuing the original plan. Sanjeev Dyamannavar, a noted rail expert, argues that the window of opportunity may have closed. "There's no point in pursuing this project because a lot of industries have come up, and acquiring land is going to be very tedious," he stated. Dyamannavar suggests an alternative solution: building a proper bypass line at Bangarpet and quadrupling the tracks at Whitefield. This alternative infrastructure, he contends, could serve the same purpose of creating a direct link without the herculean task of acquiring densely developed land.

The core issue extends beyond this single project. The Whitefield-Kolar line is one of five railway projects in Karnataka where construction work has not even begun due to land hurdles. The situation is similarly dire for the Belagavi-Dharwad, Shivamogga-Harihar, and Hassan-Belur lines, where no land has been acquired. For the 96-km Shivamogga-Rannebennur line, only about half of the needed land is in hand.

A State-Wide Land Acquisition Challenge

Official data paints a concerning picture of railway development in the state. Overall, sanctioned projects in Karnataka require 9,020 hectares of land. As of now, only 5,679 hectares have been acquired, leaving a massive shortfall of 3,341 hectares, which accounts for 37% of the total requirement.

In a recent statement to the Rajya Sabha, Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw highlighted the central government's readiness but pointed to the critical role of state support. "The govt of India is geared up to execute projects; however, success depends on the support of Karnataka govt," Vaishnaw said. He also provided context, noting that 65 new surveys for lines and doubling projects covering 7,239 km have been sanctioned for Karnataka in the last three years and the current financial year.

The minister clarified that post-sanction, projects face multiple challenges including land acquisition by the state, statutory clearances, and geographical conditions. The data underscores a significant bottleneck: while new projects are being planned, the execution of older, sanctioned projects remains inextricably tied to the resolution of land issues, a responsibility that largely falls on the state government. The fate of the Whitefield-Kolar line, and indeed several other crucial links, continues to hang in this balance of inter-governmental coordination.