In a fascinating twist on the understanding of cooperation, scientists at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bengaluru have discovered that severe population crashes can act as a powerful filter, weeding out selfish 'cheater' cells and promoting teamwork among bacteria. The study, published in the journal PLOS Biology, provides crucial experimental evidence on how dramatic events like floods or fires can reshape the evolutionary fate of microbial societies.

The Microbial Battle: Cooperators vs. Cheaters

Microbial communities are not just chaotic swarms; they often function through sophisticated cooperation. Individual bacterial cells can expend precious energy and resources to perform tasks that benefit the entire group, such as hunting for food or forming protective structures. However, this altruistic system is inherently vulnerable. It invites exploitation by 'cheater' cells that reap the rewards of communal effort without contributing anything themselves. For decades, evolutionary biologists have theorized that sudden, drastic reductions in population size—known as population bottlenecks—might help control this cheating. The IISc team set out to test this theory in the lab.

Jyotsna Kalathera, former PhD student at IISc's Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology and the study's first author, explains the concept: "A population bottleneck refers to a drastic and sudden reduction in both the size and diversity of the population. If there are ways to purge out cheaters from the population, this would be one of the ideal ways to do it."

Stringent vs. Relaxed Bottlenecks: A Tale of Two Outcomes

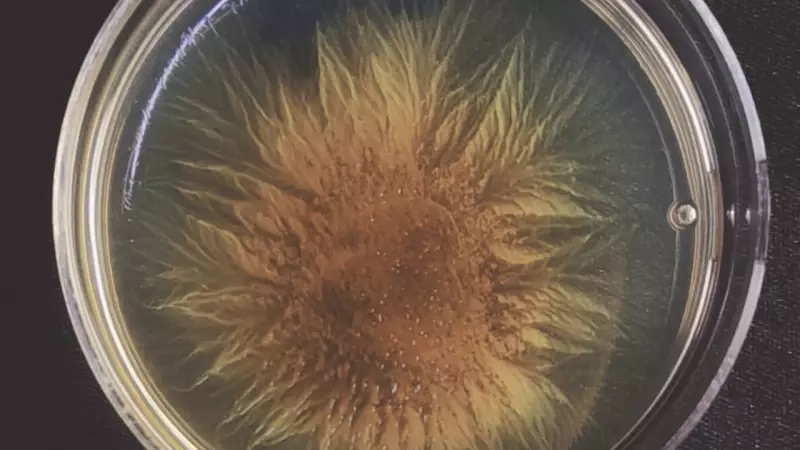

The researchers used the social bacterium Myxococcus xanthus as their model. This microbe is famous for its coordinated 'wolf-pack' hunting and its ability to form complex, multicellular fruiting bodies filled with spores during starvation. Through long-term evolution experiments, the team subjected bacterial populations to repeated cycles of bottlenecks with varying severity.

They compared two main scenarios:

- Stringent Bottlenecks: Only a very small number of cells survived each cycle.

- Relaxed Bottlenecks: A much larger number of cells survived each cycle.

The team meticulously tracked four key cooperative traits: sporulation (forming spores), germination (spores reviving), predation (group hunting), and growth.

The results were striking. Under stringent bottlenecks, traits directly linked to survival and reproduction—specifically sporulation and growth—were strongly favoured. In contrast, abilities like predation and germination declined. This evolutionary pressure led to more uniform populations dominated by highly cooperative individuals, as cheaters had fewer places to hide.

Conversely, relaxed bottlenecks produced the opposite effect. With more survivors, greater genetic variation persisted, and intense competition for resources emerged throughout the bacterium's life cycle. This environment allowed cheater strategies to linger and even thrive.

Broader Implications for Nature and Medicine

Samay Pande, Assistant Professor at IISc and the study's corresponding author, highlights the relevance to natural ecosystems. "These kinds of drastic reductions happen in nature too, during floods or forest fires. Microorganisms allow us to test ideas that are difficult to study in larger ecosystems," he said.

While the genetic underpinnings of these evolutionary shifts have been identified, the precise molecular mechanisms remain a subject for future research. Nevertheless, the findings offer profound insights into a fundamental biological puzzle: how is cooperation maintained in a competitive world?

"Cooperation is central to the evolution of life itself," Pande added. "From genes forming chromosomes to cells forming multicellular organisms, collaboration is unavoidable, but it is never free."

This research has significant practical implications. Understanding how cooperation stabilises in microbial communities can shed light on:

- The dynamics of chronic bacterial infections, where cheater cells can undermine group virulence.

- The evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance, often a cooperative trait.

- The management of beneficial microbial communities in agriculture and industry.

The IISc study, therefore, moves beyond theoretical biology, providing a framework to understand and potentially manipulate microbial societies for human health and environmental benefit.