The sound of a cricket ball meeting a bat in the subcontinent often carries echoes beyond the boundary ropes. Today, it can signal diplomatic frost or heated rivalry. But there was a time, not too long ago, when this very sound was a symbol of shared struggle, brotherhood, and a united front against a common cricketing adversary.

The United Front: When Arch-Rivals Became Allies

In the 1980s and 1990s, the dynamics between Indian and Pakistani cricketers were starkly different from the current tense standoffs. Players from both sides didn't just exchange formal handshakes; they shared hugs, inside jokes, and even post-match social hours. This camaraderie extended to the highest levels of administration, where board officials fought side-by-side against a pervasive bias in the sport's global governance.

The International Cricket Council (ICC) at the time operated under a blatantly biased rulebook that favoured the traditional Anglo-Aussie axis. Major tournaments like the World Cup were permanently slated for England, and the old guard held disproportionate voting power, including a veto. This inequitable system sowed the seeds for a historic revolt, one that would be led by an unlikely Indo-Pak duo.

The Biryani Pact at Lord's: A Subcontinental Eureka Moment

The catalyst for change came less than 24 hours after Kapil Dev lifted the 1983 World Cup at Lord's. The euphoria of India's victory was tempered with frustration for NKP Salve, then president of the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI). He was aggrieved by the English hosts' refusal to provide him with a few extra passes or even paid tickets for the final.

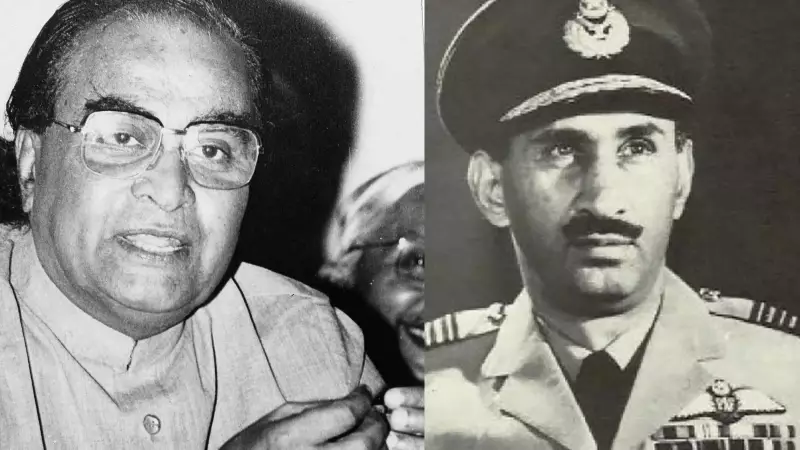

Over lunch in the Lord's dining area, Salve shared his grievance with his Pakistani counterpart, retired Air Chief Marshal Nur Khan. This was a remarkable meeting given their histories: Salve was a Lok Sabha MP during the 1965 war, while Khan was the Pakistan Air Force's commander-in-chief in the same conflict. Yet, their commitment to cricket transcended political and military allegiances.

As they lamented the dismissive treatment, an exasperated Nur Khan posed a revolutionary question: "Why can't we play the next World Cup in our countries?" This was Asia's eureka moment. By 1984, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka had formed a troika and won a joint bid to host the 1987 Reliance World Cup.

The Financial Masterstroke and the Power Shift

Their winning strategy was a financial masterstroke that outmaneuvered the established powers. The Asian consortium promised each ICC permanent member £200,000, nearly four times what England was offering. Crucially, India and Pakistan declared they would not seek any hosting funds from the ICC itself—an unprecedented offer that made the deal irresistible.

The success of the 1987 Reliance Cup was an epochal moment. It proved the commercial might of subcontinental cricket and permanently altered the sport's power equations. The financial tap for Indian cricket was turned on, leading to the cascading wealth the BCCI commands today. This momentum was later carried forward by visionaries like Jagmohan Dalmiya, who played a key role in shifting the ICC headquarters from London to Dubai, established the Asian Cricket Council, and championed Bangladesh's Test status.

However, this meteoric rise has been shadowed by a tragic forgetting. As India's coffers swelled and its voice became dominant at the ICC—culminating in an uncontested presidency for BCCI's Jay Shah—the old bonds of solidarity have frayed. Cricket, once a bridge, is now often wielded as a political weapon against neighbours like Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The narrative has shifted from collective ascent to solitary supremacy. In climbing to the summit of world cricket, India risks forgetting the shoulders it stood upon—the neighbours who were brothers-in-arms in the crucial fight for a fair and democratic sport. The very commitment to cricket that built its prosperity now seems secondary to narrower, more isolationist priorities.