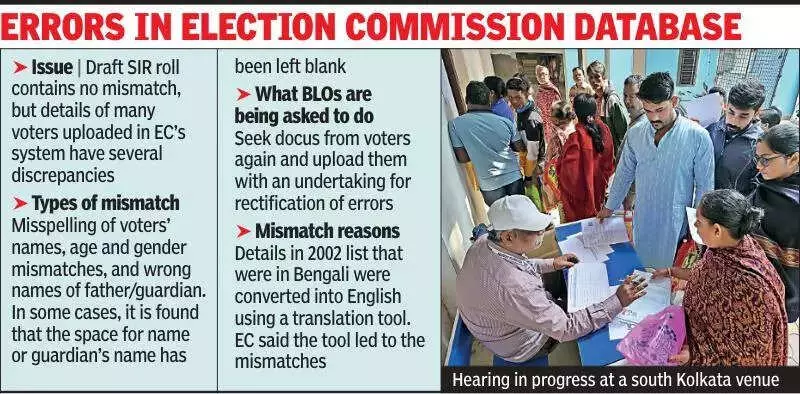

In Kolkata, a significant administrative hurdle has emerged in the electoral process, putting Booth Level Officers (BLOs) in a difficult position. Despite a draft Special Summary Revision (SIR) roll showing no mismatches, the Election Commission's (EC) central database reportedly contains numerous discrepancies in voter details. This has forced BLOs to embark on another round of door-to-door visits to collect documents for corrections, often facing the wrath of confused and agitated voters.

Technical Glitches Cause Widespread Data Mismatch

The core of the problem lies in technical errors within the EC's system. After identifying a mismatch between the hard copy draft SIR list and the digital database, the EC instructed BLOs to gather documents again for rectification. The discrepancies are not minor; they range from critical errors like misspelled voter names, incorrect age and gender, and wrong father's or guardian's names. In some alarming instances, the system shows the name or guardian's name field as completely blank, even though BLOs had correctly uploaded all these details during the initial enumeration process.

An official explained the likely source of the error: the hard copy of the 2002 SIR list was scanned and uploaded, and details originally in Bengali were converted to English using a translation tool. "This caused the mismatch for which the voters have been marked in the category of 'logical discrepancies'," the official stated. This categorization mandates a fresh upload of documents to fix the errors.

BLOs Bear the Brunt of Public Anger

The task of correction has fallen on the BLOs, who are now facing considerable hostility from the public. Voters, who have already verified their correct details in the draft roll, are understandably frustrated at being asked to submit the same documents again for a mistake they did not make. This frustration is often directed at the BLOs, the most visible representatives of the electoral machinery on the ground.

A BLO from Tollygunge, tasked with rectifying 15 discrepancies on a Wednesday night, expressed his helplessness: "We are at the receiving end of public ire even though the errors were not made by us." He added that voters are getting agitated when asked to repeat the submission process. The situation has escalated in some cases, with another BLO recounting how a voter, upon being informed of the name mismatch in the system, threatened to file a court case against him. "It is difficult to persuade the person to submit his documents again so that I can correct his name in the system through the BLO App. I can understand the reason behind the anguish," said the BLO, who is dealing with over 200 such discrepant cases.

Specific Cases Highlight Systemic Issues

The scale and nature of the errors are varied. A BLO in north Kolkata provided concrete examples, stating, "I have 20 voters whose names or guardian's names are showing errors in the system. One of my voters is 44, but the system shows her age as 88. I will need her documents again." This instance underscores how fundamental data points have been corrupted, necessitating a labor-intensive verification drive.

The directive for fresh door-to-door visits has also raised safety concerns among BLOs. Many have already faced ill-treatment at some households during earlier rounds, and the current atmosphere of public anger makes them fearful of further backlash when they knock on doors again. They are caught between the EC's instructions to clean the database and the on-ground reality of dealing with inconvenienced citizens.

This episode highlights the critical challenges in managing large-scale digital voter databases and the human cost of technical failures. The success of the rectification drive now hinges on convincing voters to cooperate once more, while ensuring the safety and morale of the frontline BLOs tasked with executing it.