Prime Minister Narendra Modi has launched a decisive campaign to dismantle the colonial legacy of Thomas Babington Macaulay, setting an ambitious 10-year timeline to reverse what he described as a damaging educational philosophy that has cost India heavily. During the Sixth Ramnath Goenka Lecture in New Delhi, the Prime Minister marked the approaching 200th anniversary of Macaulay's influential campaign with a strong critique of its enduring impact.

The Colonial Legacy Under Scrutiny

Prime Minister Modi specifically referenced Macaulay's famous speech, identifying what he called the colonial administrator's "biggest crime" - creating Indians who "are Indians by appearance but British at heart." The Prime Minister argued that this philosophical foundation has broken the nation's self-confidence while instilling a persistent sense of inferiority among its people.

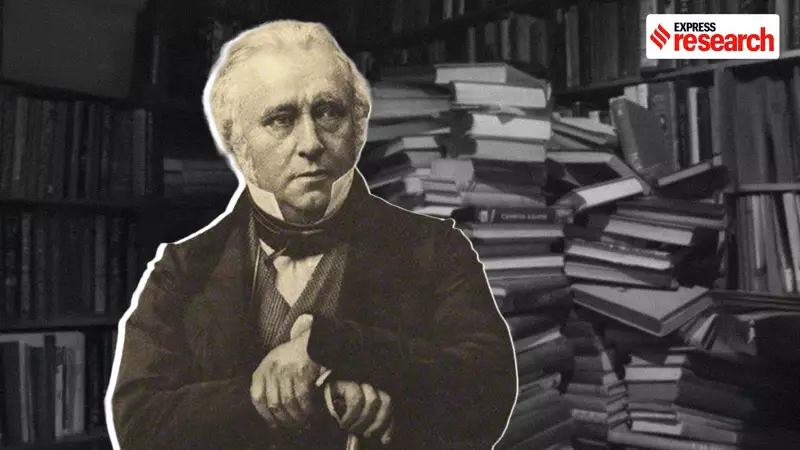

Even 166 years after his death, Macaulay's influence continues to shape South Asian society in profound ways. His legacy permeates everything from educational materials children study to legal frameworks interpreted in courts across the region. The Latin inscription beneath his statue at Trinity College, Cambridge University celebrates his role in reforming India's letters and laws, a testament to his enduring colonial impact.

Macaulay's Formative Years and Indian Appointment

Thomas Babington Macaulay was born on October 25, 1800 and grew up as the eldest of eight siblings. According to author Parimala V Rao's work Beyond Macaulay: Education in India, 1780-1860 published in 2020, Macaulay experienced significant childhood trauma when he was sent to a private boarding school at age 13. These experiences of familial separation and school bullying likely shaped both his strong family attachments and his aggressive approach toward opponents.

Macaulay's educational journey saw him master Greek and Latin during his school years before joining Cambridge at 18 to study law. He became a Parliament member at 30, and in a notable contradiction, later argued that British civil servants bound for India would benefit more from learning tribal languages than the classical dead languages he himself had mastered.

His deep engagement with Indian affairs began in 1832 during British Parliament debates about renewing the East India Company's Charter. Rao's research highlights Macaulay's expressed regret that Parliament paid less attention to Indian developments than to minor domestic incidents in England.

Legal Reforms and the Indian Penal Code

Macaulay's appointment as law member positioned him to draft what would become the Indian Penal Code (IPC). Despite describing his legal experience as limited to prosecuting a boy for stealing poultry, Macaulay brought his Cambridge legal training and political acumen to the task.

Chakshu Roy, an expert on legislative procedures, notes that Macaulay championed significant reforms including press freedom and reducing privileges for British settlers who could appeal to Calcutta's Supreme Court. As chairman of the law commission established by the Charter Act, Macaulay embarked on consolidating India's criminal laws, resulting in the Civil Procedure Code (1859), Indian Penal Code (1860), and Criminal Procedure Code (1861).

Macaulay completed the IPC draft in 1837, though it only came into force in 1862. Historian Robert E. Sullivan emphasizes in Macaulay: The Tragedy of Power that this penal code not only governed India but also influenced legal systems across former British territories, with provisions like the criminalization of sodomy persisting long after independence.

The Education Revolution and Its Consequences

Macaulay's most enduring legacy emerged from his role in India's education system. When he arrived in India, the General Committee of Public Instruction was deadlocked between Orientalists favoring Indian languages and literature and Anglicists supporting European ideas and English education.

Governor-General William Bentinck resolved this impasse by appointing Macaulay as President of the Committee of Public Instruction. This position enabled Macaulay to produce his famous Minute of 2 February 1835, often described as the 'Manifesto of English Education in India.'

In this pivotal document, Macaulay articulated his vision: "We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern—a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect."

This philosophy led the government to adopt English as the primary medium of instruction in schools and colleges. The approach prioritized establishing elite English institutions over developing widespread elementary education, effectively neglecting mass education in favor of creating an Anglicized administrative class.

Prime Minister Modi's current campaign directly targets this 200-year educational legacy, seeking to reverse what his government perceives as a fundamental distortion of India's cultural and educational identity. The 10-year reform timeline represents one of the most significant attempts to decolonize India's education system since independence.