In the open plaza of Mumbai's oldest museum, a 20-metre-long cloth wall sways gently. From afar, it resembles a giant curtain. A closer look reveals a partition: one side adorned with orderly plant prints, the other marked by chaotic, termite-like patterns. This is the entry point to 'Salt Lines', an exhibition that resurrects the memory of a colossal, forgotten botanical border that once stretched across India.

The Thorny Barrier of Colonial Control

At the heart of the show is the Inland Customs Line, a 4,000-km boundary built by the British in the 19th century to enforce a crippling salt tax. Artist duo Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser, known as Hylozoic/Desires, present their first Indian solo exhibition, created with RMZ Foundation and India Art Fair and supported by Alkazi Foundation. The project focuses on the hedge's 2,500-km living section, famously called 'The Great Hedge of India'.

Stretching from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal, this barrier was designed to be "utterly impassable to man or beast." Built initially by the East India Company and later maintained by the British Raj, its purpose was to stop smugglers from moving untaxed coastal salt into British territories. "We first stumbled upon this incredible history during research on salt," the artists admit. "Its scale shocked us. It seemed improbable that such a large botanical infrastructure existed without everyone knowing."

Building and Policing a Living Wall

After Robert Clive's 1757 victory at Plassey, salt transformed into a major revenue stream for the Empire. The British imposed monopolies, forcing people to buy salt at inflated prices from government depots. To secure this income, they constructed the hedge.

It began as a crude fence of thorny branches. From the 1860s, under officials like A.O. Hume, it became a living hedge. Teams planted hardy native shrubs—babool, Indian plum, karonda, prickly pear—dug trenches, built embankments, and maintained a patrol road. By 1869, it spanned over 2,300 miles from the Indus to the Mahanadi, skirting Delhi, passing Agra, Jhansi, and terminating in present-day Odisha.

At its peak, the hedge stood 12 feet high and 14 feet thick, woven with thorny creepers. Where plants wouldn't grow, stone walls were erected. Nearly 14,000 men were employed to guard and maintain it, one of the largest security operations in the subcontinent. Hume himself compared it to the Great Wall of China, calling it the "chiefest safeguard."

Art, Archives, and Erasure

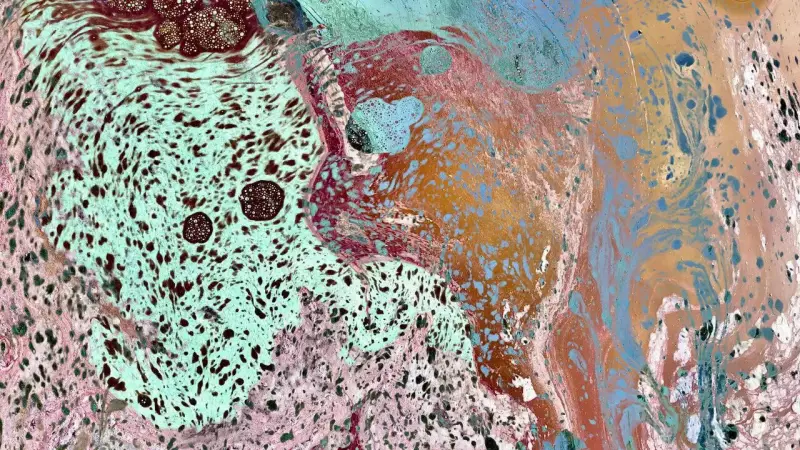

The artists found the hedge was missing from visual history. "We found textual evidence in the National Archives of India and the British Library, but no imagery," they say. To fill this gap, 'Salt Lines' presents speculative records: re-enactments at Sambhar Lake (a key salt outpost) and AI-generated images, printed using a 19th-century salt process and toned with gold.

The centrepiece is a 23-minute film, 'The Hedge of Halomancy' (2025). It follows Mayalee, a courtesan who historically resisted the British by refusing to replace her traditional salt stipend with cash. Salt here is both material and metaphor, linking her story to Hume and, symbolically, to Gandhi's Dandi March.

So, how did this massive structure vanish? Nature struck first. Termites, winds, rats, and tigers damaged it. Human anger followed; during the 1857 rebellion, parts were burnt down. Finally, when the British gained control over sources like Sambhar Lake, taxing salt at its origin became cheaper. The expensive hedge was officially dismantled on April 1, 1879. Villagers carted away the deadwood, embankments eroded, and nature reclaimed the land.

The hedge faded from memory until British writer Roy Moxham rediscovered it in the 1990s, tracing its remnants for his book 'The Great Hedge of India'. He noted the profound human cost, revealing how the salt tax worsened famines and how guards worked in harsh isolation. "It was a terrible discovery to find it was constructed to cut off an affordable supply of an absolute necessity of life," Moxham concluded.

Recent years have seen renewed interest, like in 2022 when runner Hannah Cox traced its path by running 100 marathons in 100 days. The exhibition's location is poignant: the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum, built in 1857 as the Victoria & Albert Museum, Bombay. Managing trustee Tasneem Zakaria Mehta says 'Salt Lines' lets the museum engage with colonial extraction and those who harvested salt.

As visitors leave, the artists offer a final reflection on their mission: to rigorously research, then "enter into the missing gaps of history and the doubt of the future, and imagine how else we can be."