For Saroj Devi, a resident of Patel Nagar in Ghaziabad, turning on the tap is an act of trepidation. The water that flows out is often yellow and carries a foul smell. "I didn't even feel like washing vegetables with it," she shared, describing a routine of letting the water run and flushing pipes in a futile hope for clarity. Her ordeal, stretching over a year, is a stark reflection of a deep-seated public health crisis gripping the National Capital Region.

A Persistent Pattern of Contamination

Official health data reveals a disturbing and persistent pattern of unsafe drinking water in Ghaziabad. In 2025, more than a quarter of drinking water samples tested failed to meet prescribed quality standards. Out of 2,003 samples analysed, coliform bacteria—a key indicator of faecal contamination—were detected in 539, rendering nearly 27% of them unsafe.

This is not an isolated annual spike. Data from the past five years shows failure rates fluctuating between 20% and 30%. While 2023 saw a brief dip to just over one-fifth unsatisfactory samples, the percentage climbed again in the following years. As testing volumes expanded, the absolute number of contaminated samples rose steadily, peaking in 2025.

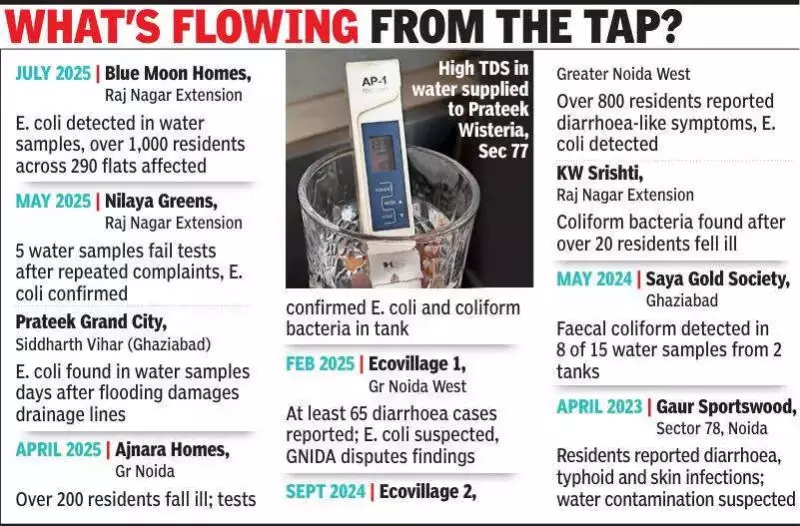

The problem manifests acutely in residential societies. In July 2024, E. coli was confirmed in water at Blue Moon Homes in Raj Nagar Extension, affecting nearly 1,000 residents. Just weeks prior, Nilaya Greens Society in the same area reported "unsatisfactory" results following complaints of foul-smelling, discoloured water. Contamination incidents were also recorded at Prateek Grand City in Siddharth Vihar after flooding, and at societies like KW Srishti and Saya Gold.

Neighbouring Noida and Greater Noida: A Reactive Approach

The situation in the densely populated, rapidly urbanising cities of Noida and Greater Noida is, arguably, more concerning due to a lack of proactive oversight. Officials admit there is no routine system to test drinking water in Noida. A senior health department official revealed, "Water samples are collected only when there is a complaint." Noida lacks its own water testing lab, and oversight is divided among industrial development agencies. Over two years, only three or four official tests were conducted in the district, with samples sent to outside labs.

The consequences of this reactive approach are severe and visible. In February 2025, at least 65 diarrhoea cases were reported at Ecovillage 1, allegedly linked to contaminated water. Earlier, in September 2024, over 800 residents of Ecovillage 2 fell ill with diarrhoea-like symptoms from water confirmed to contain E. coli. As far back as April 2023, residents of Gaur Sportswood in Noida reported diarrhoea, typhoid, and skin infections linked to suspected water contamination.

"The water often looks muddy and has a strange odour," said Rita Mittal, a resident of Ajnara Homes in Greater Noida. "Even after installing filters, the fear of contamination doesn't go away." Her society saw over 200 residents fall ill in April 2024, with tests later confirming E. coli and coliform in the underground water tank.

Systemic Failures and Ageing Infrastructure

Health officials and resident welfare groups point to systemic failures and crumbling infrastructure as the root cause. While housing society bylaws mandate regular tank cleaning and water testing, enforcement is virtually non-existent. "On paper, societies are supposed to clean tanks and test water regularly," an official said. "But there is very little monitoring and almost no accountability."

KK Jain, secretary general of the Federation of Noida Resident Welfare Associations, highlighted the institutional failure. "There are no routine inspections by Noida or any other authority. Water is tested only after complaints come in. By then, people have already fallen sick." He identified ageing infrastructure as the core issue, noting that in many sectors, 15 to 20-year-old sewer and water pipelines run close together, often at the same depth. "Leakage and mixing happen at the supply end. In sectors like 39, 37, 51, 47 and 82, sewer-related problems are extremely serious."

Dr RK Gupta, district surveillance officer in Ghaziabad, concurred that contamination is rarely an isolated lapse. "These contaminations happen due to systemic failures," he stated. Factors include open or damaged overhead tank lids allowing bird and insect entry, infrequent tank cleaning, and the hazardous proximity of ageing sewer and water lines, which makes cross-contamination inevitable when leaks occur.

The data, the outbreaks, and the daily anxiety of residents like Saroj Devi paint a clear picture: the water crisis in Ghaziabad, Noida, and Greater Noida is a chronic public health emergency driven by institutional neglect and decaying infrastructure, demanding immediate and comprehensive action.