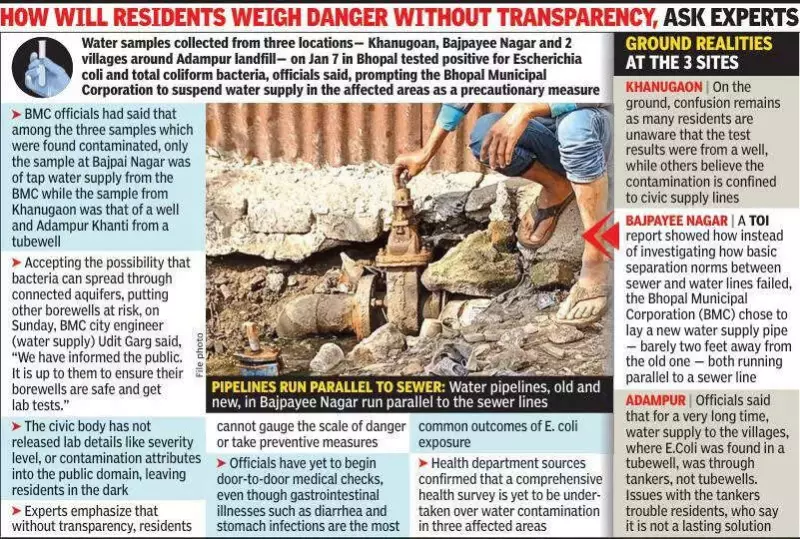

A public health crisis is unfolding in parts of Bhopal as residents, left without clear guidance, continue to draw drinking water from potentially unsafe sources days after the Bhopal Municipal Corporation (BMC) confirmed E. coli contamination in a well in Khanugoan. Despite the known risks of gastrointestinal illnesses, a comprehensive health survey and door-to-door checks are yet to begin, leaving the community vulnerable.

Official Inaction and Public Confusion

Almost a week after the contamination was confirmed, the civic body's response has shifted responsibility to the public. BMC city engineer for water supply, Udit Garg, stated on Sunday that while the possibility of bacteria spreading through connected aquifers is accepted, it is now up to households to ensure their borewells are safe and get lab tests. Crucially, the BMC has not released detailed lab reports indicating the severity level or specific contamination attributes, keeping residents in the dark about the true scale of the danger.

Community Backlash and Inter-Agency Blame

Local representatives have strongly rejected the BMC's stance. Mohammed Zaheer, aide to corporator Rehana Sultan, argued that it is not feasible for every household to arrange private testing. He insisted that the BMC must proactively check all borewells and wells. Zaheer also pointed a finger at inter-agency accountability, noting that the sewage line suspected of causing the contamination falls under the Public Health Engineering (PHE) department.

Concerns are also mounting about the potential fallout of wider testing. An aide to a Congress corporator revealed unease, noting that nearly 2,000 of the area's 15,000 residents are already disconnected from the direct supply line. He warned that more extensive testing could expose a larger crisis, highlighting that the contaminated well previously supplied water equivalent to 60 tankers, a gap now only partially bridged by 10–15 tankers.

A Looming Health Emergency

Health department sources confirmed that a comprehensive health survey across the three affected areas—Khanugoan, villages near Adampur, and Bajpayee Nagar—is still pending. This is despite the fact that exposure to E. coli commonly leads to diarrhea and stomach infections. Speaking off the record, a district health official acknowledged the contamination could spread beyond a single well and agreed that wider testing across multiple sites is necessary.

The current situation presents a dangerous paradox: residents are aware of contamination in one well but lack the resources and information to assess the safety of their alternatives. Experts stress that without transparency and proactive government intervention, the community remains at significant risk, turning a water contamination issue into a full-blown public health emergency.