In the wake of a water contamination scare in Indore, the Bhopal Municipal Corporation (BMC) swiftly initiated extensive testing of its own tap water supply. The results, gathered over four consecutive days of rigorous sampling, have revealed a surprising and positive picture for the state capital's residents.

Test Results Reveal Premium Quality Water

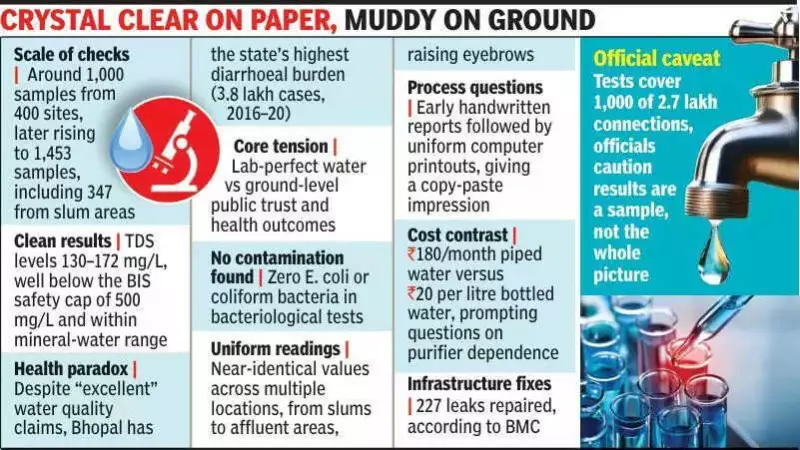

The civic body collected close to 1,000 water samples from 400 different sites across the city, including areas within slums. The analysis focused on key parameters like Total Dissolved Solids (TDS), pH balance, and bacteriological presence. The findings were striking.

The TDS levels across all samples ranged between 130 to 172 milligrams per litre (mg/L). This range is not only well within the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) safety cap of 500 mg/L but squarely places Bhopal's tap water in the mineral-water category. For context, the World Health Organization (WHO) considers TDS below 300 mg/L as 'excellent' for drinking.

Furthermore, the physical and chemical parameters were balanced, with pH levels hovering around a neutral 7. Crucially, bacteriological tests found no trace of harmful E. coli or coliform bacteria. BMC City Engineer Udit Garg reported that by a subsequent Tuesday, the number of tested samples had risen to 1,453, all confirming the excellent quality.

A Stark Contrast to Other Cities and a Public Health Paradox

The quality of Bhopal's municipal water stands in sharp relief when compared to other major Indian cities. While Bhopal's TDS stays below 172 mg/L, Delhi's tap water runs between 250–1,200 mg/L, Indore averages 425–1,350 mg/L, and Gurugram's groundwater can spike past a staggering 5,000 mg/L.

These results naturally spark a significant question for consumers: If piped water supply costs just Rs 180 per month, is there a need to pay Rs 20 per litre for packaged water or invest in expensive purifier filters? The test data suggests the tap water mirrors premium bottled water specifications.

However, this narrative of 'excellent' water quality exists alongside a concerning public health report. The State Action Plan for Climate Change & Human Health, Madhya Pradesh (revised 2022), identifies Bhopal as the district with the heaviest diarrhoeal burden in the state. From 2016 to 2020, the capital logged 3.8 lakh acute diarrhoea cases, far outpacing other districts. The plan highlights Bhopal as an epicentre for reported water-borne illnesses, exposing a vulnerability that seems at odds with the recent water quality reports.

Officials Stand by Data Amid Scrutiny

City Engineer Udit Garg insists that all testing protocols were strictly followed, even in areas considered suspect. He cautions, however, that the findings, while extensive, represent just 1,000 checks out of the city's 2.7 lakh water connections.

When asked if the state capital's tap water is better than bottled, Garg did not deny the possibility, choosing instead to stand firmly by the official reports. He also noted that alongside the testing drive, the corporation had already repaired 227 leaks at various sites to maintain system integrity.

The testing process itself evolved during the four-day campaign. The initial reports on January 1 came as handwritten sheets from a single analyst covering about 40 locations. By the second day, the reports transitioned to neat computerized printouts. The consistency of the data—rows of near-identical numbers—initially gave a copy-paste impression, which the digital versions later reinforced, painting a picture of uniform perfection.

For now, Bhopal's residents have received reassuring data about the fundamental quality of their water. Yet, the disconnect between this data and the city's high incidence of water-borne diseases suggests that quality at the source is only one part of a larger safety equation that includes last-mile delivery and storage.