Durjoy Datta Speaks Candidly About Creative Boundaries and Modern Pressures

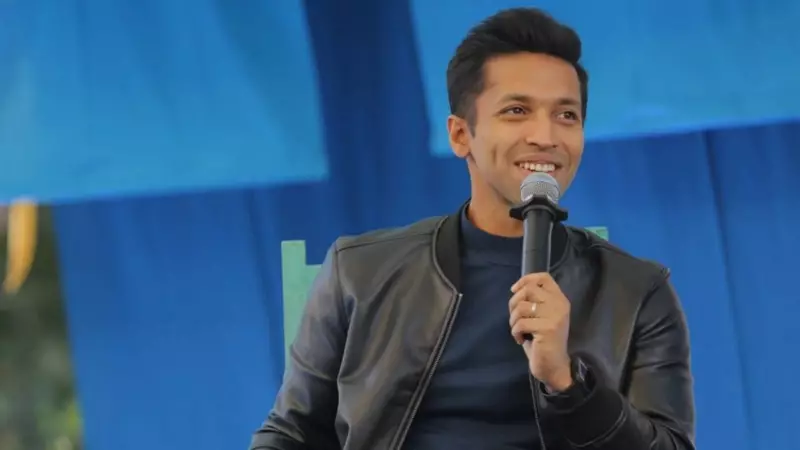

Bestselling author Durjoy Datta recently shared his thoughts on creative limitation, genre frustration, social media fatigue, and the evolving nature of critical validation. The conversation took place at a book signing event in Mumbai, where Datta engaged with an audience spanning different age groups.

A Room Full of Contrasts

The Mumbai bookstore buzzed with anticipation before Durjoy Datta arrived. Attendees ranged from people in their late twenties and thirties to college students with backpacks. Datta entered the room after everyone settled, apologizing for the delay with a lighthearted joke about his children not cooperating during the morning routine.

He immediately asked how many people had read his latest book, While We Wait. When only a few hands went up, he laughed and suggested that those who hadn't should purchase the book, read it, and share their thoughts with him directly via email.

The Theme of Limitation

Throughout the discussion, Datta repeatedly returned to the theme of limitation. He acknowledged both external constraints and self-imposed boundaries that shape his creative process.

When questioned about potentially moving away from romance writing, Datta clarified that romance remains central to his work. However, he expressed a long-standing desire to explore other genres.

"My childhood dream has been to write a fantasy novel," he revealed, explaining why that dream remains unfulfilled. According to Datta, writing thrillers or fantasy in India comes with specific expectations that feel creatively restrictive.

"With thrillers there is a problem, you cannot Indianise Swedish novel writing," he noted. Fantasy brings its own constraints, he added, often requiring incorporation of Hindu mythological elements to gain acceptance.

Self-Critical Reflections

Datta's self-critical tone became particularly evident when he considered how his younger self would view his current work.

"I think I'd be self-critical," he stated without hesitation. Referring to his earlier book The Boy Who Loved, he remarked, "I take it as a half-baked book now."

Social Media Discomfort

The conversation shifted to Datta's relationship with social media, particularly Instagram. He described feeling like an imposter on the platform for an extended period.

"For the longest time, I felt like an imposter on Instagram," he confessed, recalling when the platform served primarily as a space for life announcements and updates.

He noted how the platform has transformed, now expecting users to create entertaining content like cooking videos and lip-syncs. "Woh bol raha hai; all these announcements are okay, par ab tu naachke dikha," he said, drawing laughter from the audience.

Datta admitted to coasting for two or three years, occasionally posting jokes but avoiding trends entirely. He only began engaging more seriously after discovering storytelling reels, though the transition felt uneasy.

"I don't consider myself a very serious writer, but I am a writer nonetheless; and I spend a year writing a book," he explained. "Now suddenly I'm supposed to take a one-minute reel seriously."

Even when his reels achieved viral success, the satisfaction remained elusive. "I could see the numbers but not feel very happy about it," he shared. "I cannot wake up thinking I need to create a reel. I can wake up thinking the entire night about a book."

The Emotional Weight of Books Versus Reels

Datta emphasized the different emotional investments he makes in books compared to social media content.

"Even if my reel is at 10 million, I couldn't truly feel happy about it," he stated. Books carry emotional weight for him, while reels do not. With books, he can analyze what worked and why, but with reels, the process feels random.

"With reels, I never know what people like. It's like throwing darts in the air," he described.

He expressed particular frustration with comparison culture on social media. With books, comparing himself to other writers leads him to spend time reading their work and often appreciating it. With reels, the response is quicker and harsher.

"I'll just think, what is this nonsense getting so many views?" he said, adding dryly, "And I am too old to be falling into that trap."

On Modern Dating and Authenticity

When the discussion turned to modern dating, Datta acknowledged that his books might not connect with contemporary relationship dynamics.

"I don't think my books connect anymore," he admitted, explaining that he no longer writes about dating apps or modern relationship mechanics because doing so would feel inauthentic.

"I don't know how these things pan out," he said. "My protagonists have already sworn off dating apps. And only meets people in real life, where the rules are set by him."

He argued that the fundamentals of love remain unchanged despite technological additions. "The basics of people falling in love and reacting in relationships are the same. Some tools have been added."

Datta acknowledged he could replicate modern dynamics if he chose to. "I can fake it. It's not very difficult," he said, before quickly adding, "But because it's inauthentic, I don't write it."

Critical Validation and Literary Recognition

The conversation concluded with Datta's thoughts on critical validation, where he expressed unequivocal views.

"I have never gotten critical validation," he stated plainly. "I knew I would never get it."

He clarified that this doesn't mean he has stopped trying to improve. "I'm deeply self-critical, and I try to get better with every book."

However, he questioned the current value of literary acclaim. "You need to write a certain kind of book to even be eligible," he observed, adding that he has found some critically validated books unreadable.

As a reader first, he finds the distinction increasingly hollow. "If I get a prize tomorrow, will I be happy? Yes. Will 70 per cent of it be for showing off? Yes. Critical validation has lost a lot of value in my head."