Gig Work Transforms Household Labor for Women in India

Household work has finally entered India's booming online platform economy. This sector, once reliant on migrant networks and cash payments, now features algorithm-managed, GPS-tracked, on-demand services. For the women who form the backbone of these apps, gig work presents a mixed reality. It offers freedom and predictable income for some, while others struggle with visibility and stigma.

A Morning in Noida: Pink Uniforms and Tea Breaks

On a cold December morning, eight women gathered under an overbridge in Noida's Sector 76. They sipped tea from plastic cups, their bright pink uniforms standing out against the smoggy backdrop. This sidewalk served as their adda—a hangout spot between assignments from Snabbit, an app promising home chore assistance within ten minutes.

Most of these women hail from West Bengal, Bihar, or Uttar Pradesh. Their workdays stretch to twelve hours, including time spent logging on, waiting, and traveling between housing societies. Despite the long hours, they report better pay than previous jobs.

"My income has roughly doubled," said Meera, a 32-year-old from Nadia district in West Bengal. She previously worked with another home services app, where conditions were harsher. "There was no weekly off, and if we worked less than six hours, they docked our pay from the previous day."

Renu, 28, from Darbhanga in Bihar, echoed this, noting constant pressure and unexplained penalties at her old job.

Financial Gains and New Freedoms

In contrast, Snabbit offers more stability. "A twelve-hour day earns us Rs 1,000 even if there's only one order," Meera explained. Monthly earnings become predictable, with attractive incentives like a Rs 20 bonus for logging in early, weekend rates of Rs 1,200, and bonuses based on customer ratings.

These women have diverse work histories—as domestic helpers, nannies, factory workers, and office staff—but never earned more than Rs 14,000 to Rs 16,000 monthly. Sushma, 26, shared, "I made Rs 8,500 at an AC parts unit. Now, with overtime, I sometimes cross Rs 1,000 in a day."

Many entered through referrals and appreciate the anonymity gig work provides. Guddi from Lucknow said, "It's easier to work for strangers. House mistresses often take domestic workers for granted and shout at them. Here, clients are generally more restrained."

Yet, daily novelty brings its own challenges. One woman remarked, "Yahaan roz naya ghar, naye log, naye mijaaz—here it's new homes, new people, new temperaments every day."

Hidden Struggles: Uniforms and Waiting Spaces

Despite higher earnings, these women lack proper facilities. They wait on cold, dusty sidewalks between gigs. For some, the uniform becomes a unwanted identifier.

Meera pointed out, "There should be a place to change back into regular clothes. Many of us don't want everyone to know what we do. In winter, warm clothes cover the shirt, but it's hard to hide in other seasons."

About four kilometers away, in Sector 100, another group sat on plastic sheets in a park. They instinctively turned their backs when residents passed by, often refusing to give their names. One woman shared, "Residents threaten to call the police. If that happens, our families will learn we work in others' homes."

These women, mostly first-time platform workers from UP and Rajasthan, viewed their uniforms with anxiety. A young woman said, "People Google the company name on our shirts. Some judge us for going to unknown homes daily, so we lie and say we do office work for the app." Many haven't told in-laws, neighbors, or even husbands about their jobs.

Waiting wears them down. One complained, "There's no shade, no restroom, no place to change... and the park is filthy. People look at us like thieves." Another recounted a harrowing experience where a client accused her of theft and made her remove sweaters for a search, only to find the missing phone under a blanket later.

Unreasonable Demands and Systemic Issues

Clients often request domestic services during holidays or for deep cleaning. Sometimes, demands exceed agreed terms. A woman in Sector 100 explained, "One-hour orders happen, but they expect three hours of washing, even men's underwear, and bathroom cleaning."

Worse, workers sometimes get reassigned to abusive clients they've reported earlier. "We have to beg the team leader to change the assignment," one said. Team leaders, responsible for specific neighborhoods, patrol on two-wheelers, ferry workers, and mediate conflicts.

The Rise of Platformized Household Work

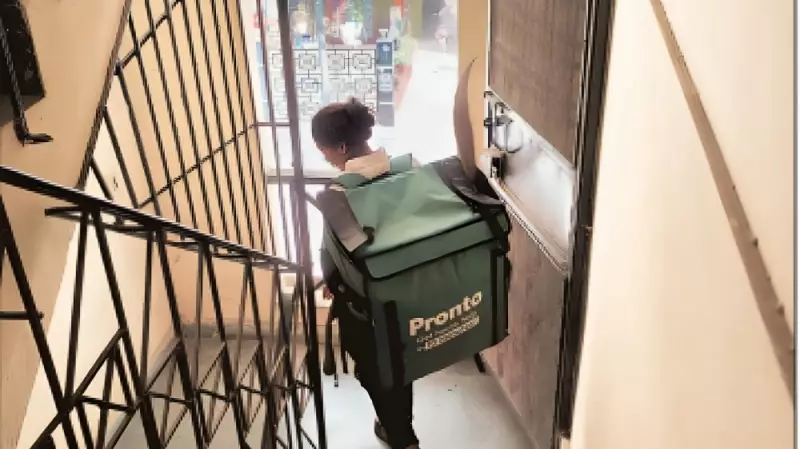

Household work was among the last sectors to join India's platform economy. Companies like Urban Company started with beauty services, expanding to cleaners and technicians. In 2024, Snabbit and Pronto entered major cities, offering managed, tracked labor in a field traditionally dependent on word-of-mouth.

Reflecting the traditional "maid" system, these apps primarily employ women. Once enrolled, workers undergo "finishing school" training. They learn professionalism, grooming, and behavior. Sushma detailed, "How to interact professionally, what to say when entering or leaving. Clothes must be clean, hair groomed—no big jewelry, a small bindi, light lip balm, daily moisturizer."

Guddi added, "You have to be professional. Not talk long on the phone, and leave no work unfinished."

Company Policies and Worker Classifications

A Snabbit spokesperson described workers as "independent contractors" and "long-term partners" with structured onboarding and training. Agreements are open-ended, terminable by either party. Payments are monthly, preferred by many workers over smaller payouts.

Performance incentives depend on customer ratings, attendance, and conduct. Snabbit didn't specify typical monthly earnings, but Pronto mentioned professionals can earn up to Rs 40,000, varying by city and bookings.

On facility complaints, Snabbit said schedules include lunch breaks, with time costs borne by the company, addressing concerns at a "micro-market level." Pronto's hubs offer seating, water, charging points, first aid, and female hygiene products, with child-friendly options in some cases.

Snabbit also provides health and accident insurance from Rs 1 lakh to 4 lakh, based on tenure and ratings.

Gig work opens doors for women in India, offering better pay and new opportunities. Yet, challenges like inadequate facilities, social stigma, and unpredictable demands remind us that progress comes with ongoing struggles. As these platforms grow, addressing worker concerns will be crucial for a fair and sustainable future.